For more than 100 years, thousands of ancient clay tablets with wedge-shaped marks have been found in the sands of Mesopotamia. These tablets have fascinated both scholars and conspiracy theorists. The world's first literate civilization made these cuneiform tablets, which hold the oldest written records of people. But what do they really mean? Are they messages from ancient gods, proof that aliens have been in touch with us, or something much less interesting? Decades of academic research have shown that the truth is more complicated and interesting than most people think.

The Beginning of Writing: What Cuneiform Really Was

Around 3200 BCE, the Sumerian city of Uruk created cuneiform script to keep track of goods and transactions in a society that was becoming more complicated. The first tablets weren't about the universe; they were lists of things like barley deliveries, livestock counts, and temple gifts. Scribes used reed styluses to make wedge-shaped marks in wet clay, which led to a writing system that lasted for more than three thousand years.

There is a lot of cuneiform literature that has survived. Archaeologists think that between 500,000 and 2 million tablets have been dug up, and the British Museum has about 130,000 of them. But only 30,000 to 100,000 have been fully translated and published, so there are still huge collections that need to be studied by scholars.

These tablets had many different uses in Mesopotamian civilization. The collection is mostly made up of administrative records, which are boring but very useful documents that cover everything from collecting taxes to maintaining temples. School tablets show how people used to learn by having students do exercises and read practice texts. Legal papers keep track of contracts, property deeds, and court decisions. Epic poems, religious hymns, and mythological stories are all examples of literary works that had an impact on cultures all over the ancient world.

The Great Literary Works: Myths That Changed the World

There are real literary treasures among the thousands of administrative tablets that show us the spiritual and intellectual life of ancient Mesopotamia. The Epic of Gilgamesh, which is preserved on twelve tablets, tells the story of a famous king's search for immortality and has one of the oldest flood stories, which is hundreds of years older than the Bible.

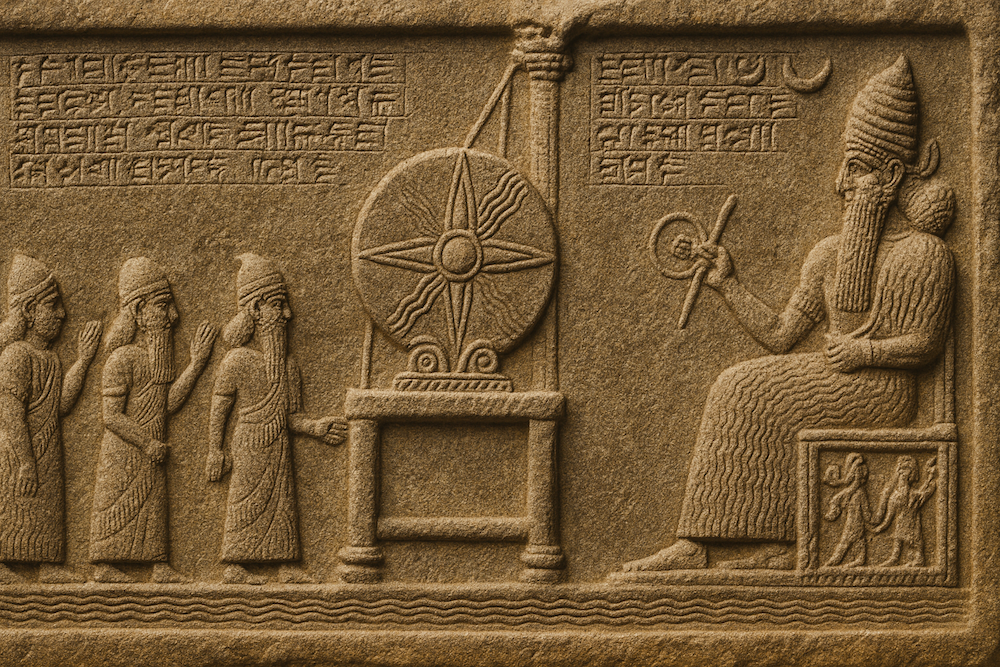

The Enuma Elish, also known as the Babylonian Creation Epic, is made up of seven tablets that tell the story of the battle between order and chaos in the universe. In this myth, the god Marduk beats the primordial sea goddess Tiamat, making the world out of her body and setting up divine order. The epic was written in Akkadian around 1200 BCE and served both religious and political purposes. It made Babylon's power official by making Marduk the head of the pantheon.

The Sumerian King List is an interesting mix of history and mythology. This document says that eight kings ruled before the flood for a total of 241,200 years. It lists rulers from the earliest times to the historical period. Modern historians say these amazing reigns are myths. The first ruler that archaeologists can prove existed was Enmebaragesi of Kish around 2600 BCE.

Religious texts elucidate Mesopotamian beliefs regarding deities, the afterlife, and humanity's position within the cosmic hierarchy. Inanna's Descent to the Underworld looks at death and rebirth, and hymns and prayers show how people worshiped in ancient temples every day. Medical books keep track of how to treat different illnesses, often mixing practical cures with magical spells.

The Anunnaki: From Gods of Old to Aliens of Today

The Anunnaki, a group of gods that show up in a lot of Mesopotamian literature, are at the heart of many conspiracy theories about Sumerian tablets. The Anunnaki are said to be the children of the sky god An (Anu) and the earth goddess Ki in real Sumerian texts. The name literally means "princely seed" or "princely blood," which means that they are divine descendants of the gods.

The Anunnaki are first mentioned during the reign of Gudea (c. 2144–2124 BCE) and the Third Dynasty of Ur. Sumerian texts say they are powerful gods who decide the fates of people, but they don't give a clear number or specific roles for them. They mostly show up in literary settings instead of being objects of organized worship, which suggests that they were more of a theological idea than real cult deities.

The contemporary metamorphosis of the Anunnaki into extraterrestrial entities is predominantly attributed to Zecharia Sitchin's endeavors, particularly his "Earth Chronicles" series, commencing with "The 12th Planet" in 1976, which recontextualized ancient myths as historical narratives of alien encounters. Sitchin said that the Anunnaki lived on a made-up planet called Nibiru and came to Earth 450,000 years ago to mine gold. They eventually used genetic engineering to make humans into slave workers.

Sitchin's Translations: Academic Critique and Cultural Impact

Mainstream scholars, archaeologists, and linguists who study ancient Mesopotamian languages have all turned down Sitchin's ideas. Critics say that his translations and methods have basic flaws that make his whole theory less strong.

Michael S. Heiser, a biblical scholar who knows a lot about ancient Semitic languages, has found many mistakes in Sitchin's translations. For instance, Sitchin translated the Sumerian word "mu" as "rocket ship," but it really means "name" or "sky." He translated "Anunnaki" as "those who came from heaven," even though the word is already well-known to mean "princely offspring."

The ancient Mesopotamians made bilingual dictionaries that don't agree with Sitchin's translations. These texts, written by Akkadian scribes to keep Sumerian words alive, give authoritative definitions that back up traditional scholarly interpretations instead of Sitchin's alien theories.

Sitchin's astronomical assertions are also unfounded. He said that Sumerian texts talk about a solar system with twelve planets, one of which is the mysterious Nibiru. But cuneiform astronomical texts always only talk about seven celestial bodies: the Sun, the Moon, and five planets that can be seen (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn). Sitchin said that the famous cylinder seal VA243 showed the solar system, but it really just shows a normal religious scene with no astronomical meaning.

Even though academics have rejected Sitchin's ideas, they have had a big impact on popular culture. Many books, movies, and online groups have adopted the ancient astronaut theory, and the TV show "Ancient Aliens" often uses his ideas. This cultural phenomenon shows how pseudoscientific ideas can become popular when they give easy answers to hard historical questions.

What the tablets actually show

The real writing on Sumerian tablets gives us interesting information about one of the first cities in human history. Records from places like Drehem show that there were complex bureaucratic systems in place to handle livestock, grain distribution, and temple offerings. One tablet from Cambridge University, which is 4,200 years old, just lists how an official named Balli gave out pig fat. This is a boring but interesting look at how things worked in the past.

Tablet houses, or schools, had educational tablets that showed how scribes learned their trade. Students did writing exercises, copied literary works, and worked on math problems. The curriculum included subjects like literature, law, medicine, and astronomy, which shows that the school system was very thorough and trained the literate elite.

Legal documents keep Mesopotamian law alive, like the famous Code of Hammurabi. These texts show advanced legal ideas like contracts, property rights, and court procedures that had an effect on legal systems all over the ancient world.

Scientific texts show that people have done great things in math, astronomy, and medicine. Babylonian astronomers came up with geometric ways to predict how planets would move. These methods weren't used in Europe until the 14th century CE. Medical texts combine real-life observations with magical practices to show how people in the past tried to figure out what was wrong with them and how to fix it.

The Strength of Mistranslation

The Sumerian tablets show how mistranslation and misinterpretation can turn old texts into modern myths. There are a number of reasons for this phenomenon:

Linguistic complexity: Cuneiform is a writing system that has been used for thousands of years to write in many different languages. Signs could be logograms (which stand for whole words), syllabograms (which stand for sounds), or determinatives (which show categories). This complexity makes it hard for even experts to translate it correctly.

Cultural distance: To understand old texts, you need to know about the history, religion, and society they were written in. Modern readers might put modern ideas onto old texts, which can lead to wrong interpretations.

Sensationalism: Claims about ancient astronauts or divine revelations that are out of the ordinary get more attention than boring administrative records. This tendency to favor sensational interpretations can overshadow academic work in public discourse.

Modern Research and Digital Preservation

Modern Mesopotamian studies use strict methods to make sure that translations are correct. Oxford University runs the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, which has searchable databases of cuneiform texts with scholarly translations and comments. Researchers from all over the world can use this resource to check claims about Sumerian literature.

Cuneiform studies are changing in big ways thanks to new technologies. 3D scanning makes digital models of tablets that are very detailed. This keeps fragile texts safe and makes them available to people all over the world. Machine learning algorithms help find patterns in cuneiform signs and make it easier to translate them. Digital archives make sure that these one-of-a-kind items will last for future generations.

New discoveries keep adding to what we know about the civilization of Mesopotamia. The ongoing excavation of sites like Tell Hariri (ancient Mari) and the study of museum collections are uncovering new things about ancient life, such as letters between diplomats and math books.

Conclusion: The Tablets' True Message

The actual "messages" found in Sumerian tablets may be more interesting than any made-up divine communication. These clay tablets keep track of the first steps people took toward writing, complex government, and living in cities. They write down the hopes, fears, and daily worries of people who lived five thousand years ago. These worries are very similar to our own.

The tablets don't show us cosmic truths from ancient astronauts; instead, they show us the basic problems that early cities had to deal with: managing resources, keeping order, passing on knowledge, and figuring out what life is all about. The true miracle does not reside in extraterrestrial intervention but in human ingenuity—the creation of writing, law, literature, and education that constitute the bedrock of all subsequent civilizations.

The ongoing interest in ancient astronaut theories shows a deeper human need to feel like we are part of something bigger than ourselves. Sitchin's interpretations are not backed by academic research, but they do raise real questions about where humans came from and where we fit in the universe. The most important thing we can learn from studying Sumerian tablets is how to tell the difference between evidence-based scholarship and interesting fiction. We should also remember that ancient people were just as human as we are, with their own strengths and weaknesses.

The clay tablets of Mesopotamia bear messages from the gods—not from aliens, but from the divine spark of human creativity that inspired our ancestors to press marks into clay and embark on the lengthy journey toward written civilization. By keeping their everyday records and great works of literature, these ancient scribes unintentionally made the first time capsule for humanity. It lets us look back in time and see ourselves in their struggles and successes.