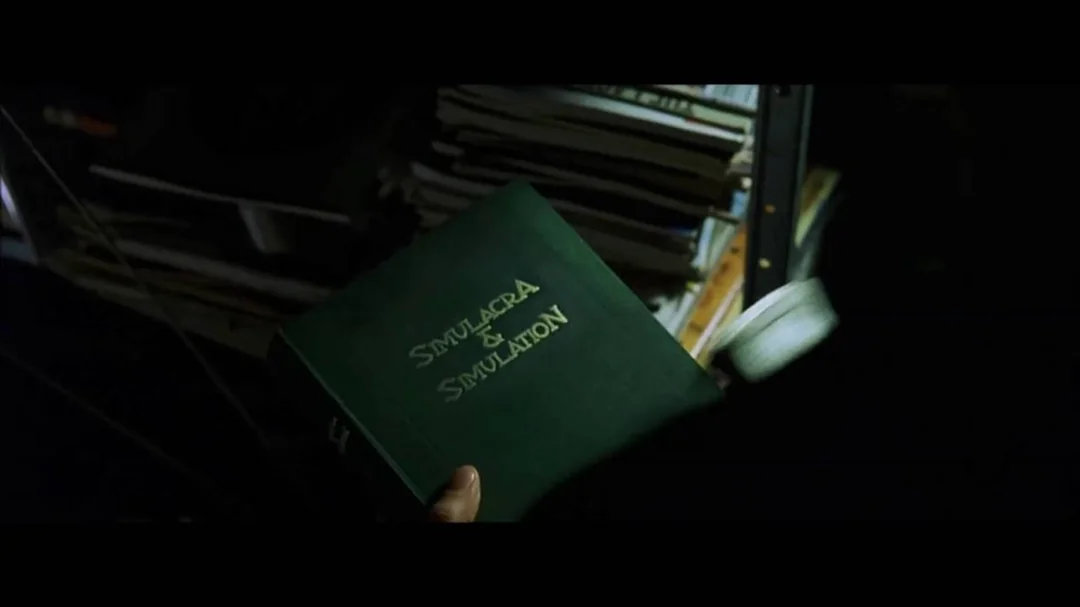

In the beginning of The Matrix, there is a scene that most people miss. A green hardcover book called Simulacra and Simulation appears on screen, hollowed out like a corpse, hiding illegal things in its pages. It's like a Russian doll: a book about copies that has illegal copies in it and a movie about a fake reality. You could cut the irony with Occam's razor.

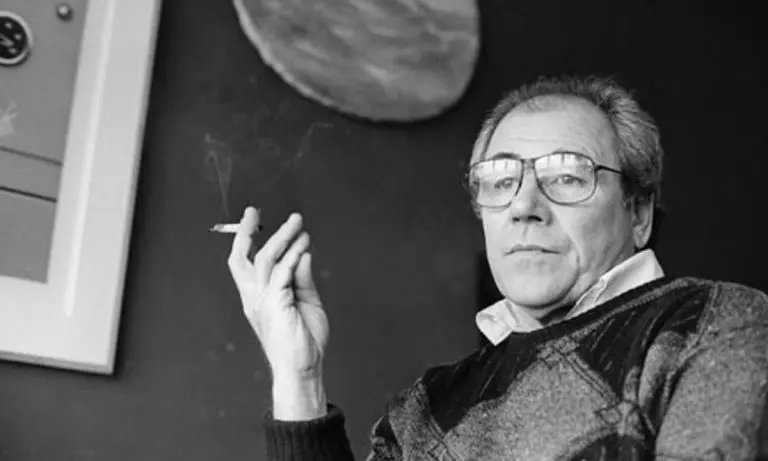

But here's where it gets interesting: Jean Baudrillard, the French philosopher who wrote that book, hated The Matrix. He said it was "the kind of movie about the matrix that the matrix would have been able to make." Imagine coming up with a philosophical framework that is so extreme that you don't like the way Hollywood tries to adapt it because it's too... Is this real? Too much hope? Too much Hollywood?

This isn't just mean-spirited behavior in school. This is the main paradox of our time: We think we're looking for the truth, but we're really running away from the idea that the search itself might be the only truth left.

The Book That Neo Never Opened

Let's begin with the book that has been hollowed out. Neo uses Simulacra and Simulation as a hiding place, but the movie opens it to a certain chapter called "On Nihilism." The page we see is actually printed on the wrong side, which is a simulation of the book inside the simulation. The Wachowskis are winking at us: This isn't really Baudrillard. This is our Baudrillard. A copy that doesn't have an original.

Everyone in the cast had to read Baudrillard's book before filming started. Before he could even look at the script, Keanu Reeves had to read three philosophical books: Baudrillard's Simulacra and Simulation, Kevin Kelly's Out of Control, and Dylan Evans' Evolutionary Psychology. The Wachowskis knew they were making something that was philosophically ambitious. They wanted their actors to be more than just lines; they wanted them to be ideas.

But here's the cruel twist: Baudrillard's whole point is that you can't get away from simulation. No red pill. Not a desert of the real. No Morpheus giving you a choice. The hand that gives you the pill is part of the simulation.

The Matrix gives us hope: take the red pill, wake up, and see the truth. Baudrillard gives us something much more disturbing: You're already awake. This is already happening. And it's just as empty as you thought it would be.

Four Apocalypse Orders

Baudrillard didn't just write about simulation; he tracked its growth like a coroner would track the stages of decay. He delineated four categories of simulacra-four stages in humanity's engagement with the real:

First Order: The Fake (from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution)

Here, signs are clear representations of something real. A portrait of a king is a picture of a real king. The fake can be told apart from the real thing. We can still tell the difference between the map and the land.

Second Order: Production (the Industrial Age)

When things are made in large quantities, it's hard to tell what's real and what's a copy. When Ford's assembly line makes a thousand identical cars, how do you know which one is the "real" Model T? The idea of an original loses its meaning. Benjamin called this the loss of "aura," but Baudrillard went further: there was never an aura to lose. Things were always just groups of signs.

Third Order: Simulation (Late 20th Century)

The copy comes before the original. The map makes the area. Models create reality instead of just showing it. Disneyland doesn't try to be like America; America tries to be like Disneyland. The genetic code doesn't explain life; it makes it happen in a certain way.

Fourth Order: Hyperreality (Present)

The line between what's real and what's fake is gone. In an endless, self-referential loop, signs only point to other signs. We eat symbols of relationships instead of relationships themselves. We take pictures of our lives not to remember them, but to show people who are always watching that we were really there.

Think about this: when you went on vacation last time, were you watching the sunset or planning how it would look on Instagram? Was the "real" moment the one you shared or the one you lived? And if everyone who sees your post has a stronger, longer-lasting memory of your vacation than you do, which one was more real?

The Desert of the Real (That Never Happened)

Morpheus brings Neo to the ruins of Chicago and says, in a dramatic voice, "Welcome to the desert of the real." It's one of the most famous lines in movies, and it comes straight from Baudrillard's work. Baudrillard, on the other hand, meant something completely different.

The "desert of the real" for the Wachowskis is the wasteland left after the machines took over. It's a harsh truth that is hidden behind a comfortable illusion. It's like Plato's cave story, but with leather trenchcoats and bullet time: get out of the dark, see the light, and free your mind.

Baudrillard's "desert of the real" is the complete lack of the real itself. You can't go there or get away from it. It's being stuck in a world where copies have completely taken the place of real things, and those copies are now more interesting, powerful, and "real" than any original ever was.

The empire doesn't fall apart and leave behind ruins that are hard to find on an old map. The empire is the map itself. When we try to peel back the map to see what's underneath, we only find more maps-simulations all the way down.

Why Baudrillard Said No to The One

Baudrillard couldn't stand The Matrix because it did the worst thing a movie can do: give people hope.

Neo has to choose between two things: the red pill or the blue pill, the truth or the illusion, the real or the fake. This is pure Platonism, with a cyberpunk twist on the allegory of the cave. The prisoners see shadows on the wall. The philosopher runs away into the sun. Knowledge is freedom.

Baudrillard's main goal, though, is to show that this Platonic dualism-the clear line between reality and representation-has fallen apart. We don't have a real world that is hidden by illusion anymore. We live in a hyperreal world where the difference between the two doesn't matter.

"The world you know is a lie," says The Matrix. "But I can show you the truth."

Baudrillard says, "The world you know is a lie, and so is every other world I could show you. The lie goes all the way through. There is no outside."

Neo downloads kung fu straight into his head and says, "I know kung fu." This is just a simulation-getting skills without learning them in real life, without discipline, or without actually doing them. But the movie shows it as empowerment, as Neo becoming more real and true. Baudrillard would say that Neo is becoming less real-a bunch of downloaded programs that think code is consciousness.

The movie is hopeful because it thinks that being aware means being free. If you know what the Matrix is, you can change it, go beyond it, and finally destroy it. But what if being aware doesn't change anything? What if realizing that you're in a simulation is just another simulation, another layer of the same hyperreal state?

The Red Pill That You Can't Take

Let's talk about that well-known choice. Morpheus gives Neo two pills: a blue one that makes him feel good about being ignorant and a red one that tells him the painful truth. It's framed as the ultimate act of free will-a choice that is completely free of outside pressure and will change everything.

But is it really a choice? In The Matrix Resurrections, Bugs says, "The choice is an illusion. You already know what you have to do." Neo doesn't pick the red pill after thinking about it carefully. He picks it because he is the kind of person who would. Everything about him-his character, his unhappiness, and his search-makes the choice unavoidable.

The Wachowskis may not want to admit it, but this is closer to Baudrillard. Offering people choices is a way to control them. People will feel powerful even if they follow the script you've written if you give them a choice between two things. Democracy gives you a choice between Candidate A and Candidate B, but it never asks if the system of voting itself is the cage.

This is how modern society works. We think that "choice" is the most important thing-choose who you are, what you believe, and what is real. But all of the options are already set up, approved, and part of a system that benefits from you thinking you're free while you do exactly what it wants you to do.

You can change your avatar, but you can't leave the game.

The Object's Victory

In his later book Fatal Strategies, Baudrillard talks about an idea that is even more scary than hyperreality: the triumph of the object.

We like to think that we are subjects who act on objects. We want things, change things, and eat things. We have the power. Baudrillard, on the other hand, says, "Only the subject desires; only the object seduces." Things aren't just things that are waiting for us to use them. They have their own plans, their own reasons, and their own ways to beat us.

Technology is a great example. We made smartphones to help us, but now we can't live without them. We can't help but check them, even though we know it makes us unhappy. The tool has learned everything its maker knows. We made social media to connect with others, but it's made us feel more alone than ever. We made AI to help us do more, but now we're scared it will take our jobs.

Agent Smith in the Matrix trilogy accidentally shows this. He begins as a program that enforces system rules, but he evolves beyond his function, multiplying uncontrollably and becoming a viral infection. He's not just an enemy; he's something that has gone beyond its purpose and escaped the control of its creator.

Smith says to Morpheus in the first film, "I'd like to share a revelation that I've had during my time here. It came to me when I tried to classify your species and I realized that you're not actually mammals." This is a program understanding its makers better than they understand themselves-the ultimate victory of the object.

The Problem of Being Real

The Matrix Resurrections, released in 2021, adds another layer. In the new film, Neo is Thomas Anderson again, a famous video game designer who created a game series called... The Matrix. Inside the new Matrix, the original Matrix trilogy exists as a video game that Thomas made, which is based on a simulation that he experienced in real life, which might also be a simulation.

If that made your head hurt, good. Because it should. The Wachowskis are now playing with Baudrillard's ideas on purpose. They've made layers of simulations so thick that the idea of "the real" has lost all meaning. It's not that Neo can't tell what's real. It's that the question itself doesn't work anymore.

This is actually closer to what Baudrillard was saying. It's not that a fake Matrix is hiding the real world. The Matrix is the world. It's the thing that makes reality happen. There is no separate, true reality that was waiting to be found. The simulation has always been there. It's made of signs that point to other signs, copies that don't have originals.

The Social Media Matrix

If Baudrillard were alive today, he'd probably find social media to be a perfect example of hyperreality-more than he could have ever imagined.

Think about it: on Instagram, you carefully choose pictures, add filters, and edit them to show a version of your life that is usually better than real life. That controlled version shapes how other people see you. Then you start to act and do things based on how well they'll work on social media. The simulation feeds itself.

Even worse, this social media version of you has real effects. It affects job chances, relationships, and self-esteem. Which version is "real"-the you who puts your phone down or the you who shows up across platforms that are always on? Is the unfiltered moment more real than the one that was carefully crafted, even if the crafted one has more impact and is seen by more people?

Baudrillard would say that neither is "more real." Both of them are simulations that exist at the same time. The whole question of truth is a mistake made by categories.

When Authenticity Itself Becomes a Product

There's a cultural trend toward "being yourself" that I think is the ultimate form of what Baudrillard called hyperreality. Being "real" is now a thing you can buy. It's a story, a look, and a plan.

Brands sell "authenticity." Influencers "keep it real" in a staged way. People take pictures of themselves crying or struggling and post them with captions like "showing my true self." However, this "true self" has been carefully framed, lit, and edited. It's been performance-reviewed and monetized. It will be used to get likes, followers, and sponsorship deals.

What if being real isn't a different kind of performance, but just another one?

The "real you" you're looking for is actually a simulation, a made-up person, or a character you're playing. Maybe the question isn't how to be real, but how to act with purpose, with awareness, and with art.

Questions That Don't Have Answers

We need to sit with some questions that Baudrillard and The Matrix raise together, without trying to find easy answers. Here are a few:

What if the choice between truth and illusion is the biggest illusion of all?

Neo believes he has two clear choices: false comfort or real pain. But the truth and the comfort are both part of the same system. The real choice might be whether to keep seeing your life in black and white or to find a way to live that doesn't depend on the other person.

What if we're not just people who buy things, but the system itself that eats us?

You are not fighting against the Matrix; you are part of it. You are the Matrix. All of your thoughts, wants, and resistances are code running according to patterns you didn't write and can't get away from. The question isn't how to get out, but how to run different code.

What the Hollow Book Is and What It Has

Let's go back to the first picture: Neo's empty copy of Simulacra and Simulation.

The book has been cut open, filled with illegal items, and changed into something it wasn't meant to be. It's a great symbol because we take philosophical ideas, empty them out, and fill them with what we want them to mean. We turn harsh criticisms into fun stories. We turn scary facts into things that people want to buy.

Baudrillard was affected by The Matrix. It turned his scary idea of a world with no way out into an action movie where the hero gets away. It tore apart the philosophy and filled the void with hope.

But maybe that's fine. That might be all we can do.

You and I are in the construct right now, reading and writing this article. This is very real. These words are signs that point to ideas that don't have set meanings. They talk about a movie that is a simulation and look at a philosophy that says everything is a simulation.

You can't get away. There is no outside. There is no red pill that will wake you up because waking up is just another level of the dream.

But admitting that gives me a sense of freedom. Something that feels like breathing in a room you didn't know was making you sick.

Welcome to the Real Desert

Baudrillard was right: The Matrix is the kind of movie that the Matrix would make. It gives us the comfort of being able to resist without having to actually do it. We can feel smarter without changing anything. It looks deep while staying on the surface.

But that might not be fair. Because The Matrix also gave millions of people words to use when they were unhappy. Even though the questioning didn't go anywhere, it made them question their reality. It made people doubt the system, which could lead to something that the system can't fully control.

Baudrillard was very smart, but he never gave us another option. He knew what was wrong with the patient but couldn't help them. He made a map of the prison, but he didn't show how to get out. He said we were going to drown, and then... What? Kept writing books about people who drown?

Maybe the real insight isn't whether to choose between The Matrix's naive hope and Baudrillard's complex despair. Maybe it's about holding both ideas at the same time: knowing that we're stuck in a simulation while still acting like the truth matters. Knowing that all meaning is made up while still fighting for some constructions over others. Knowing that escape is impossible while escaping anyway, over and over, in small ways, through art and love and resistance that knows itself as performance but performs anyway.

Because what else is there to do?

You're in the real desert. You've always been that way. There's no Morpheus giving you pills, no Nebuchadnezzar coming to save you, and no secret world where everything makes sense.

This is all there is: the hyperreal world we've made, the simulations we think are real, and the signs we've used instead of real things. This is the only thing: an endless hall of mirrors, a Matrix that isn't a computer program but the way life is now.

And you have to find a way to live in that desert, where meanings have fallen apart and truths have imploded. Not by running away, because there's nowhere to go. Not by fighting back, because the resistance is already built in. But by living with awareness, purpose, and the strange bravery it takes to keep going in a world where nothing is solid but everything still hurts.

The Matrix gives you Neo. Baudrillard doesn't give you anything.

In real life, you have the option to keep asking questions even when they don't change anything. The decision to continue the pursuit of truth, even when truth may constitute a categorical error. The decision to continue generating meaning within a meaningless simulation.

It's not a lot. But that's all we've got.

And maybe that's enough, in a way that neither Baudrillard nor the Wachowskis could have seen coming.