In the summer of 1921, Alfred Watkins, a rich businessman, stood on a hill in Herefordshire, England, and said he had a vision. He saw something amazing as he looked out over the rolling hills: ancient monuments, medieval churches, prehistoric burial mounds, and natural landmarks all seemed to line up in perfectly straight lines across the land. This moment of revelation would lead to one of the most long-lasting alternative theories in British archaeology. It started as simple trade routes and grew into mystical energy highways that are said to connect sacred sites all over the world.

Ley lines are a fascinating mix of archaeology, mysticism, and the ability of humans to see patterns. What started as a simple geographical theory about old paths has become a key part of New Age belief, mixing with UFO theories, earth energies, and spiritual practices. But underneath the layers of mystical meaning is a more down-to-earth truth that tells us as much about the ancient landscape as it does about how people think.

The Beginning of a Theory

Alfred Watkins did not study archaeology. He was born in Hereford in 1855 to a wealthy family. He became known as a photographer and inventor when he made the Watkins Bee Meter, a groundbreaking exposure meter that helped make photography a popular hobby. He had to travel a lot around Herefordshire for work, which gave him a deep understanding of the countryside that would be very important to his later theories.

Watkins was looking at a map near Blackwardine on June 30, 1921, when he saw that many old sites seemed to line up perfectly. He thought that straight lines could connect standing stones, hillforts, churches, holy wells, and other landmarks. He thought these lines were ancient trade routes or trackways. He called these alignments "ley lines," which is an Old English word for a cleared space. He saw this word in place names along the routes he suggested.

In September 1921, Watkins told the Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club about his work. In 1922, he published his first book on the subject, Early British Trackways. His most important book, The Old Straight Track, came out in 1925 and explained his theory in great detail. He suggested that prehistoric Britain was traversed by a network of straight pathways utilized for trade and ceremonial functions, originating from the Neolithic era and undoubtedly preceding Roman roads.

Watkins did not think these lines had any supernatural meaning, which was very important. Everyone said he was a smart, logical person. His theory was based on real-life examples: people in the past made straight paths through the landscape by using well-known landmarks as waypoints. He thought that surveyors he called "dodmen" made these trackways. He got this name from a dubious etymology that had to do with a local dialect.

Archaeological Rejection

The archaeological establishment was not impressed. Critics quickly pointed out a number of major flaws in Watkins' theory. First, the proposed straight lines would not have worked well for real travel, especially in hilly areas. People who have walked in the British countryside know that the shortest way to get from one place to another often means climbing steep hills or crossing dangerous rivers. Like modern-day walkers, ancient traders would have followed the natural curves of the land and stayed away from things that got in their way.

Second, and maybe worse, many of the places Watkins linked were from very different times in history. A line could connect a Neolithic burial mound, an Iron Age hillfort, and a medieval church, which are all thousands of years apart. The notion that these disparate monuments constituted a singular, orchestrated system exceeded the limits of plausibility.

The statistical argument was just as bad. Britain, especially southern England, has a very high number of historic and prehistoric sites. There are churches, burial mounds, standing stones, and other interesting places all over the landscape. If you draw a straight line in almost any direction, you will probably cross several of these points of interest by chance. Tom Williamson and Liz Bellamy proved this beyond a doubt in their book Ley Lines in Question, which came out in the 1980s. They demonstrated that the density of archaeological sites in the British landscape is so high that discovering apparent alignments is statistically unavoidable and does not substantiate intentional planning.

To show how silly it was, archaeologist Richard Atkinson made a map of "telephone box leys," showing that even modern phone booths could be connected by straight lines using the same method Watkins used. This exercise showed how dangerous confirmation bias is: if you look for patterns with enough data points, you'll always find them.

The Revival of the 1960s and the Mystical Change

Watkins died in 1935, and his ideas might have been forgotten if it weren't for a huge revival in the 1960s. This resurrection came with a huge change that would have probably upset the rational businessman. Tony Wedd, a former RAF pilot and UFO fan who wrote a booklet called Skyways and Landmarks in 1961, started the revival. Wedd said that ley lines weren't old trade routes at all; they were beacons for spaceships from other planets.

Wedd had been influenced by French ufologist Aimé Michel, who said that UFO sightings in France followed straight-line patterns he called "orthotenies." Wedd combined this with Watkins' ley lines and claims from people who said they had been abducted by aliens that UFOs used Earth's magnetic fields to navigate. He came to the conclusion that ancient people had set up ley lines to guide visiting spacecraft.

John Michell's 1969 book The View Over Atlantis made the idea very popular. Historian Ronald Hutton called it "almost the founding document of the modern earth mysteries movement." Michell, who was part of the counterculture and hung out with The Rolling Stones, turned ley lines from ordinary paths into mystical energy channels. He used Chinese ideas about feng shui and dragon lines to suggest that an advanced ancient civilization once covered a lot of the world and built ley lines to use the spiritual energy that flows through the Earth.

Michell's work came at the right time in history. The counterculture of the 1960s accepted anything that went against traditional science and reason. Ley lines became linked to the beginning of the Age of Aquarius, earth energies, psychic phenomena, and ancient knowledge that has been lost to modern materialism. The Ley Hunter magazine started in 1965, and a group of fans began using maps, compasses, and dowsing rods to search the British countryside for these supposed energy lines.

This New Age view was very different from Watkins' original idea. He had suggested simple paths for getting around, but Michell and his followers thought of rivers of mystical power connecting sacred sites and channels of earth energy that only those with spiritual sensitivity could feel. Some people who believed in ley lines said that sleeping at places along them gave them prophetic dreams or changed their state of mind. Some people used dowsing to map what they thought were invisible energy currents that scientific tools couldn't see.

Famous Examples

The St. Michael Line is the most famous example of a supposed ley line. It runs about 364 miles across southern England, from St. Michael's Mount in Cornwall to Hopton-on-Sea in Norfolk. It is said that it goes through or near many important places, such as Glastonbury Tor, Burrowbridge Mump, Avebury, and several churches dedicated to St. Michael. Supporters say that the line follows the sun's path on May 8, which is the spring festival of St. Michael.

People who are interested in this also talk about a "Mary Line" that supposedly goes around the Michael Line. The two lines are said to represent masculine solar and feminine lunar energies. In their book The Sun and the Serpent, dowsers Paul Broadhurst and Hamish Miller wrote about their journey along these lines, saying that they felt different energy signatures at different places.

Another alignment that comes up a lot connects Stonehenge, Glastonbury Tor, and Avebury in a perfect right-angled triangle. People who believe this see the precise geometry as proof of ancient surveying skills and careful planning. But skeptics say that when there are a lot of old sites close together, geometric relationships are unavoidable and don't mean anything.

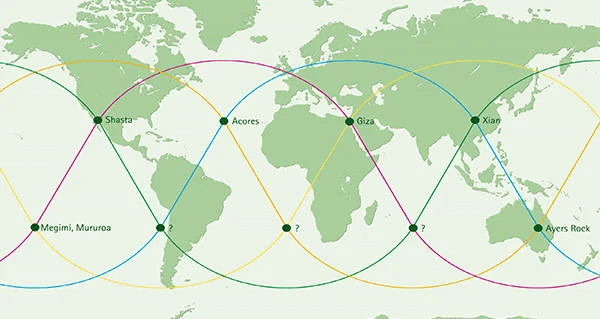

People who are interested in ley lines have spread the idea far beyond Britain. They say that a grid of lines connects famous monuments around the world, like the Egyptian Pyramids, Machu Picchu, Stonehenge, Uluru, and others. Most of the time, these claims are based on choosing famous places and drawing lines between them on flat map projections. They don't take into account the fact that the Earth is curved and that these structures were built by different cultures that were thousands of miles and years apart.

The Scientific Decision

From a scientific point of view, ley lines don't really exist. Many studies have shown beyond a doubt that the apparent alignments are not evidence of ancient planning or mystical energies, but rather random chance, selective observation, and cognitive bias.

The statistical issue persists as insurmountable. There are thousands of ancient sites in the British landscape, so straight lines that connect several landmarks are not proof of design but rather a mathematical fact. A researcher can make "ley lines" that look real by carefully choosing which sites to include and which to leave out. When supporters of ley lines show their alignments, they always leave out the many sites that don't fit their proposed lines.

The problem with the timeline is just as bad. Ley line maps often link places that are thousands of years apart, like Neolithic henges, Bronze Age burial mounds, Iron Age hillforts, Roman roads, Saxon churches, and Norman castles. The idea that all of these structures, which were built by different cultures for different reasons over thousands of years, were all placed according to one master plan goes against both logic and archaeological evidence.

Most importantly, no scientific tool has ever been able to measure the "earth energies" that people who believe in ley lines say they can find. Magnetometers, which can pick up small changes in magnetic fields, have been used a lot at places where ley lines are said to be. They have never shown anything like the straight energy flows that dowsers talk about. The Dragon Project was set up in the 1970s to look for scientific proof of earth energies at prehistoric sites. It ran for decades without finding any reliable data to back up ley line theories.

Dowsing, the main way to "find" ley lines, has been tested many times in controlled settings and has never been shown to work better than chance. The ideomotor effect, not an outside force, is what makes dowsing rods move. This is now known.

The Science of Recognizing Patterns

Why do so many people believe in ley lines if they don't exist? The answer lies in basic parts of how people think, especially how well we can recognize patterns. Our brains developed the ability to recognize patterns in our surroundings, which is essential for survival. But this same skill can make us see meaningful patterns in random data, which psychologists call apophenia or pareidolia.

When we look at a map with a lot of historical sites on it, our brains naturally try to find connections and make sense of things. When you draw lines between landmarks, you make patterns that are satisfying and seem like they were made on purpose. This is how our brains work to see faces in clouds, constellations in random star patterns, or hidden messages in static noise.

Ley lines also provide a deeper sense of connection to ancient wisdom and secret knowledge. In a world that is becoming more complicated and secular, the idea that our ancestors knew secret things about earth energies is a comforting story about lost knowledge. It implies that enigmas exist beyond the grasp of traditional science, attainable solely by individuals possessing spiritual awareness or open-mindedness.

The experiential dimension of ley hunting fortifies belief. Walking through ancient landscapes, seeing prehistoric monuments, and trying to feel mystical energies can all be very moving experiences. People who believe in earth energies say that the combination of physical activity, natural beauty, a historic setting, and anticipation can lead to strong emotional responses. Just because these things really happened doesn't mean that the reason they happened is real; people don't need a supernatural explanation for their ability to feel awe and connect to a place.

Effect on Culture

Ley lines have had a big cultural impact, even though they aren't scientifically valid. They have become a part of popular culture and have inspired writers, musicians, and artists. Richard Long and Hamish Fulton were two artists who were part of the land art movement in the 1970s. They were inspired by ideas about landscape alignment and sacred geography. According to ley line theories, the Glastonbury music festival put its pyramid stage in a certain place.

Ley lines are often used in fantasy books, video games, and movies as places where magic can be found. This fictional treatment is a more honest way to deal with the idea than pseudoscientific claims, since it sees ley lines as imaginary rather than real things.

Ley lines are often used in rituals and sacred geography in modern Paganism and New Age spirituality, which is another way the idea has affected these groups. Glastonbury is on the supposed St. Michael Line and has become a center for alternative spirituality, in part because of its connection to ley line theories. This spiritual use may be important to those who practice it, but it is not the same as making a claim about ancient construction or measurable energies.

The Lasting Appeal

Ley lines are still fascinating to people more than a hundred years after Alfred Watkins' discovery on a hillside, even though there is a lot of evidence that they don't exist. This persistence shows us something important about people: our need for mystery, meaning, and a link to the past often outweighs our commitment to facts and logical thinking.

The ley line phenomenon shows that ideas can change in ways that the person who came up with them didn't mean for them to. Watkins put forward a testable archaeological hypothesis regarding ancient pathways. This hypothesis should have been abandoned when evidence did not support it. Instead, it became a spiritual belief system that couldn't be proven wrong because believers said they had special knowledge that only they could access.

This change isn't just happening to ley lines. Many pseudoscientific beliefs follow a similar pattern: an idea that seems reasonable at first but is wrong becomes popular, changes to include supernatural elements that make it impossible to prove wrong, and stays around because it meets psychological needs that facts can't satisfy.

But maybe there is more to ley hunting than just being right. The practice encourages people to look at their surroundings, pay attention to old buildings, and think about how people and the land are connected. Walking from one historic site to another, whether or not you follow a "ley line," can help you appreciate both the beauty of nature and the history of your culture. If ley line belief inspires individuals to connect with history and landscape in personally significant manners, it may possess intrinsic value, irrespective of mystical energies.

The key is to keep the difference between what feels important and what is objectively true. Ley lines can be seen as cultural ideas and imaginative ideas without being seen as real things. The ancient sites they say they connect are truly amazing works of human creativity and hard work that don't need any supernatural explanation to make people wonder.

Ley lines ultimately reveal more about our own identity than about the ancient world. They show how well we can recognize patterns, how much we want to know what's going on, and how willing we are to see what we want to see. There are many amazing things in the landscape, but they are the amazing things that come from nature, human achievement, and the deep history written in stone and earth, not invisible energy lines that guide spacecraft or channel cosmic forces.

The real magic isn't in mystical alignments; it's in the fact that people always want to connect with the past, find meaning in the world around them, and believe that there is more to the world than what we can see and touch. Ley lines, regardless of their factual validity, remind us that the boundary between skepticism and imagination, as well as between evidence and belief, is an intriguing domain deserving of exploration with both diligence and modesty.