In the heart of the Amazon rainforest lies one of archaeology's most enduring mysteries—where legend meets reality and obsession transcends time

The Lost City of Z is one of archaeology's most enduring mysteries. It is hidden deep in the Amazon rainforest. For more than a hundred years, this legendary civilization has sparked people's imaginations and led to many expeditions, books, and movies. What started as the obsession of one British explorer has grown into a fascinating story that fills the gap between myth and reality and changes how we think about ancient Amazonian civilizations.

The Beginning of an Obsession

Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett, a British geographer, cartographer, and explorer born in Torquay, Devon, in 1867, is the main character in the story of the Lost City of Z. Fawcett was different from many of his fellow explorers because his family had a long history of adventure. His father was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and his brother was a well-known mountain climber and philosopher.

The Royal Geographical Society hired Fawcett in 1906 to map the mostly unknown borderlands between Brazil and Bolivia. This was the start of his journey to South America. This job would change his life because it showed him the amazing variety of life in the Amazon and the tantalizing hints of ancient civilizations that once thrived in this "empty" wilderness.

Fawcett went on seven big trips to the Amazon basin between 1906 and 1924. He was very good at dealing with native people, unlike many European explorers of his time. He often used gifts, patience, and polite behavior instead of force. His trips were good for science because he found the sources of several rivers, mapped hundreds of miles of unexplored jungle, and made detailed geographical observations that helped map South America.

The Manuscript That Changed Everything

Fawcett's belief in the Lost City of Z wasn't just based on romantic ideas. His beliefs were bolstered by the discovery of Manuscript 512, an enigmatic 18th-century Portuguese document located in Brazil's National Library in Rio de Janeiro. This interesting text, which is thought to have been written by Portuguese bandeirante João da Silva Guimarães, tells the story of how ancient ruins were found in 1753.

The manuscript painted a picture of a beautiful stone city that looked like it belonged in the classical Mediterranean. It talked about big streets, beautiful arches, big plazas, fountains, and temples with hieroglyphic writing on them. Most interestingly, the document talked about building styles that seemed impossible for native Amazonian cultures, at least from the European point of view at the time.

The manuscript says that the Portuguese explorers found this ruined city while looking for the legendary mines of Muribeca, which is Brazil's version of El Dorado. They said the city they found was completely empty, with beautiful stone houses that had no furniture or people in them. It was as if everyone had just disappeared into the jungle.

Fawcett's Ideas and Methods

Fawcett had come up with a full theory about the lost civilization he called "Z" by 1914. He was different from many treasure hunters of his time in that he took his search very seriously. He talked to a lot of native people, recorded their stories, and carefully looked at old documents. His research led him to believe that there was a complex civilization in Brazil's Mato Grosso region, close to the headwaters of the Xingu River, before Columbus arrived.

Fawcett's theory was groundbreaking for its time. Most archaeologists thought that the Amazon rainforest was too dangerous for large groups of people or advanced civilizations to live in. People called the area a "fake paradise" because it looked nice but couldn't support urban growth. Fawcett disagreed with this view, saying that the many Spanish conquistador accounts of big settlements and advanced indigenous societies couldn't all be made up.

Hiram Bingham III's rediscovery of Machu Picchu in 1911 gave him more confidence. It showed that big ancient cities could stay hidden in South America's far-off areas for hundreds of years. Fawcett thought that if such a beautiful complex could be lost in the Peruvian Andes, it could also be lost in the Brazilian Amazon.

The Last Expedition and the Disappearance

Fawcett was able to get support for what would become his most famous and last expedition, even though academics were skeptical and he was having trouble with money. On April 20, 1925, he left Cuiabá, Brazil, with his 21-year-old son Jack and Jack's best friend, Raleigh Rimmel. The expedition got a lot of attention, and newspapers were eager to hear regular updates from the jungle.

Fawcett thought the party traveled light because they only brought what they needed: two Brazilian workers, horses, mules, and dogs. Fawcett was sure that his years of experience and the people he had chosen to be with him would help him succeed. His letters home showed that he was hopeful.

"You need have no fear of any failure..."

The last message from the expedition came on May 29, 1925, in a letter written from a place Fawcett called "Dead Horse Camp." This place got its name because a horse died there during Fawcett's 1920 expedition. The letter showed that he was ready to go into uncharted territory with only Jack and Rimmel, having gotten rid of the Brazilian guides.

Percy Fawcett, his son, and Raleigh Rimmel all disappeared without a trace after May 29, 1925. In January 1927, almost two years after their last message, the Royal Geographical Society officially said they were lost.

The Search and Ideas

The disappearance of such a famous explorer got a lot of attention around the world and led to many rescue attempts. Over the next few decades, interesting clues came to light: in 1927, a nameplate with Fawcett's name on it was found; in 1933, a theodolite (a surveying tool) was found; and in 1979, what was said to be his signet ring was found. But none of these artifacts gave clear proof of what happened to the expedition.

People came up with different ideas about what happened to them. Some people thought that hostile native tribes killed them, while others thought that they died from disease or starvation. Some romantic theories said that Fawcett had decided to "go native" and live with the native people. Some people even thought he had found his lost city and decided to stay there.

In 2005, journalist David Grann looked into the mystery for The New Yorker magazine. He then wrote the bestselling book "The Lost City of Z" (2009) based on his research. Grann's research took him to see the Kalapalo people, who were one of the last native groups to meet Fawcett's expedition. The Kalapalo had oral histories about Fawcett's group that talked about how they had warned the explorers about hostile tribes to the east but were not listened to. These stories say that the Kalapalo saw smoke from Fawcett's campfires for five days after the expedition left their village. After that, the smoke stopped, which means that the explorers probably died.

New Discoveries in Archaeology

Even though Fawcett's "City of Z" was never found, modern archaeology has proven many of his main ideas about Amazonian civilizations to be true. Advanced technologies, especially LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), have completely changed how we think about pre-Columbian Amazon societies.

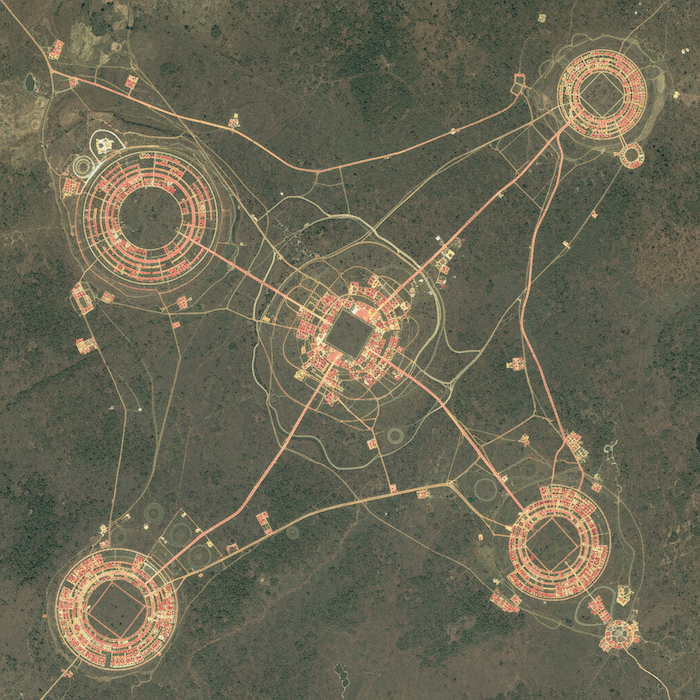

The Kuhikugu archaeological complex is the most important find that backs up Fawcett's theories. Anthropologist Michael Heckenberger and the local Kuikuro people were the first to study it scientifically. Kuhikugu is a huge urban complex that used to house about 50,000 people over an area of 7,700 square miles. It is in the upper Xingu River region where Fawcett was looking.

The Kuhikugu civilization, which lasted from about 1,500 years ago to about 400 years ago, had advanced city planning that included:

- Interconnected settlements connected by raised roads and canals for canoes

- Advanced water management with dams, fish ponds, and systems for watering plants

- Defensive structures like moats and palisades around towns and cities

- Big public spaces with plazas that are up to 150 meters wide

- Monumental architecture built horizontally instead of vertically, like the pyramids of the Maya and Aztecs

The civilization fell apart in the early 1600s, probably because of diseases brought by Europeans, even though there may not have been any direct contact for decades. The jungle had already started to take back the abandoned settlements by the time Europeans got there.

LiDAR and New Findings

Recent LiDAR surveys of the Amazon basin have found even more proof of ancient cities. Archaeologists have found the advanced Casarabe Culture (500–1400 CE) in Bolivia's Llanos de Mojos region. This culture built large cities with monumental platform and pyramid architecture linked by raised causeways that went on for miles.

These findings have shown:

- Huge size of pre-Columbian settlements that were not known before

- Advanced engineering like systems for controlling water and networks for moving people and goods

- A complicated social structure that can plan and carry out big construction projects

- Environmental modification that shows these societies actively managed their forest resources

Similar discoveries have been made all over the Amazon, from ancient geometric earthworks (geoglyphs) in Brazil's Acre state to urban areas in Ecuador. These findings show that the Amazon was not a "empty" wilderness, but rather a place where millions of people lived in advanced, long-lasting civilizations.

The Scientific Justification

Modern archaeology has confirmed that Fawcett's core hypothesis was correct: the Amazon rainforest once hosted large, complex civilizations capable of monumental architecture and sophisticated urban planning. But these societies were native American civilizations, not the Mediterranean or European colonies that Fawcett sometimes thought about.

The collapse of these civilizations was not due to some mysterious catastrophe but rather the devastating impact of Old World diseases introduced by European contact. The indigenous population of the Americas is thought to have dropped by 90% after Europeans arrived. The Amazon was hit especially hard because it had a lot of people living there and was more likely to get sick from epidemics.

Effects on the Environment and History

The discovery of large pre-Columbian civilizations in the Amazon has big effects on how we think about how people and the environment interact. These societies created ways to manage forests that were good for the environment and allowed for large populations. The well-known "terra preta" (black earth) found all over the Amazon is mostly the result of traditional farming methods that made the soil more fertile.

This knowledge challenges Western assumptions about wilderness and conservation, suggesting that the Amazon we see today is not pristine nature but rather a landscape still recovering from the demographic collapse of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Cultural Legacy and Modern Interpretation

The story of the Lost City of Z has become a powerful cultural metaphor for humanity's relationship with the unknown. Fawcett's quest shows how noble scientific exploration can be and how dangerous it can be to get too obsessed. His story has inspired:

- Literary works including Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Lost World" (1912)

- "The Lost City of Z" (2009) by David Grann is one of the most popular modern books

- Hollywood movies, like the 2016 version with Charlie Hunnam

- Documentaries that look into both the historical mystery and new archaeological finds

Lessons from the Quest

The Lost City of Z teaches us a lot that will last:

Scientific Persistence: Fawcett's belief that there were complex civilizations in the Amazon, even though academics were skeptical, has been mostly proven correct by modern archaeology.

Cultural Humility: The story makes us think about what we think we know about how indigenous people can do things and how they interact with the environment.

Technological Revolution: New tools like LiDAR are changing the way we see things in forests that people have been in.

Interdisciplinary Cooperation: The most important recent discoveries have come from archaeologists, indigenous communities, and technology experts working together.

The Mystery That Keeps Going

We now know that Fawcett was mostly right about Amazonian civilizations, but there are still some mysteries:

- Fawcett's exact fate continues to be of interest to researchers and adventurers

- Historians still argue about whether Manuscript 512 is real

- Undiscovered sites are probably still hidden under the trees

- Indigenous oral histories may contain additional clues to ancient settlements

Relevance Today

The story of The Lost City of Z is still relevant today because the Amazon is facing unprecedented threats from climate change, deforestation, and development pressure. Learning about the area's long history of people makes conservation efforts more important and shows how important it is to protect both natural ecosystems and the indigenous communities that still have ties to this ancient heritage.

The archaeological finds that came from Fawcett's search show that the Amazon is not only a place with a lot of different plants and animals, but also one of the most important archaeological sites in the world. This dual significance—ecological and cultural—fortifies the case for extensive safeguarding of the rainforest.

Conclusion: Between Truth and Myth

The Lost City of Z is one of the most interesting stories about exploration because it connects romantic adventure with scientific discovery. Percy Fawcett's obsessive search, which cost him his life, led to a revolutionary understanding of pre-Columbian American civilizations.

Fawcett never discovered his particular "Z," but his belief that advanced civilizations once thrived in the Amazon has been unequivocally validated. He did find the lost cities he was looking for. They weren't European colonies or Mediterranean outposts; they were amazing indigenous civilizations that learned how to live in one of the most difficult places on Earth.

The story reminds us that there are still mysteries in the world worth pursuing, that indigenous knowledge systems hold deep wisdom, and that our understanding of what people can do and how they interact with the environment is always changing. Fawcett helped us find something that may be even more valuable than the Lost City of Z: a deeper understanding of how complex and advanced pre-Columbian American civilizations were and how people and the natural world interact.

As we deal with environmental problems around the world, the sustainable ways of life of these "lost" civilizations can teach us a lot. What started as one man's obsession with a mythical city has turned into a bigger understanding of what people can do and how we interact with the world around us. This makes it one of the most important archaeological stories of the modern era.