Operation Mockingbird is one of the most controversial and long-lasting spy programs from the Cold War. This supposed secret campaign by the Central Intelligence Agency tried to use American news media for propaganda purposes, which blurred the lines between journalism and intelligence work in ways that still make people distrust media institutions today.

How a Secret Program Started

The story of Operation Mockingbird starts after World War II, when the US had to deal with a new enemy: the Soviet Union. The Cold War was more than just a military conflict; it was also an ideological battleground where the hearts and minds of people were the ultimate goal. In this situation, the CIA knew that changing the story through the media could be just as powerful as any weapon.

Frank Wisner became the head of the Office of Policy Coordination in 1948. This was a secret operations unit set up by the US National Security Council. The OPC got help from the CIA at first, but it was under the State Department's control, which gave it a lot of freedom to run psychological warfare operations. There are different stories about when Wisner started what would become known as Operation Mockingbird that same year, but the exact timing is still up for debate.

Wisner was the only person who could do this job. He had worked for the Office of Strategic Services during World War II and seen how powerful propaganda and psychological operations could be. He was sure that strong countermeasures were needed to stop the spread of communism after seeing Soviet troops take over Eastern Europe at the end of the war in Romania. He thought that the media would be an important place to fight in this war.

How Media Manipulation Works

The way Mockingbird worked was both complex and sneaky. The program didn't just plant false stories or directly control what editors wrote. Instead, it focused on building relationships with powerful journalists, editors, and media executives. These relationships worked on many levels, from clear paid agreements to unspoken agreements where doing one's duty as a citizen and doing one's job well were the same thing.

Documents and testimonies that came out later showed that the CIA hired top American journalists to work for what was basically a propaganda network. Some journalists were paid directly for their help. Some people worked with intelligence agencies because they believed it was their duty to do so. Others saw practical benefits, like getting exclusive information or help with their reporting in other countries.

The program reached even the most respected news organizations in the United States. Author Deborah Davis says that by the early 1950s, Frank Wisner had made friends with respected people at The New York Times, Newsweek, CBS, and other major news organizations. Cord Meyer became a key player in managing these media relationships after he joined the CIA in 1951.

The jobs given to journalist-operatives were very different from each other. Some people only worked for the CIA as "eyes and ears," telling them what they saw while they were on foreign assignments. Some people did more than just sit back and watch. They planted stories that were good for the CIA, protected CIA agents, or acted as go-betweens with intelligence sources in Communist countries. In some cases, big news organizations knowingly gave CIA employees cover by giving them jobs as stringers or clerical staff in foreign bureaus.

The Guatemala Operation: What Mockingbird Did

The overthrow of Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz in 1954 was one of the most important uses of Operation Mockingbird's powers. The operation showed how covert action could be used with media manipulation to reach foreign policy goals.

Frank Wisner was in charge of the Office of Policy Coordination and was in charge of what came to be known as Operation Success. There were many parts to the campaign against Arbenz. It was said that media figures like Henry Luce, the powerful founder of Time magazine, could stop stories that were too sympathetic to Arbenz from being published. People say that Allen Dulles, who became head of the CIA in 1953, stopped left-wing journalists from going to Guatemala to cover the situation. One of these journalists was Sydney Gruson of The New York Times.

This joint effort between intelligence operations and media control showed how powerful Mockingbird was at its peak. The CIA made sure that the public and politicians supported the overthrow of a democratically elected government by controlling the story about what was happening in Guatemala.

Investigation and Exposure

The CIA and American media may have kept their close ties secret forever if it weren't for the political unrest of the 1970s. The Watergate scandal and the news that came out after it about government spying programs made it possible to ask questions about the actions of intelligence agencies that had never been asked before.

The CIA had to write a report in 1973 called the "Family Jewels" that listed a number of questionable things the agency had done. This document mentioned a "Project Mockingbird" that involved wiretapping journalists in 1963, but it didn't go into detail about the larger media manipulation program that would later be known as Operation Mockingbird.

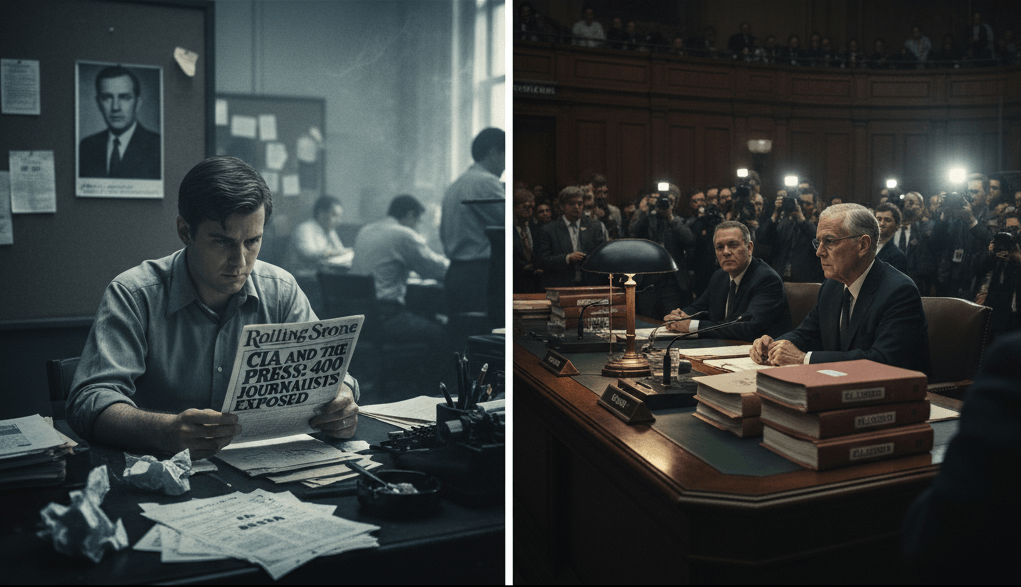

The Church Committee investigations of 1975 were the real turning point. The Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities was set up on January 27, 1975, after shocking news about CIA activities came to light. Senator Frank Church of Idaho led the committee, which had never before had such easy access to classified materials and talked to intelligence officials at length.

The Church Committee's investigation confirmed what many people had already thought: the CIA had indeed built relationships with private groups, including the media. The committee found proof that fifty journalists had official but secret ties to the CIA. But later, critics said that the committee's final report downplayed how bad these relationships were and protected the most well-known media figures and organizations that were involved.

The Bernstein Exposé

If the Church Committee's investigation opened a door, journalist Carl Bernstein kicked it wide open. Bernstein had just won the Watergate case at The Washington Post. In 1977, he spent six months looking into the relationship between the CIA and the press during the Cold War.

On October 20, 1977, Rolling Stone magazine published a 25,000-word cover story about his findings that caused a lot of trouble. Bernstein said that over the past 25 years, more than 400 American journalists had worked for the CIA without anyone knowing. Some of the most respected names in American journalism were among them, including columnists, foreign correspondents, and Pulitzer Prize winners.

Bernstein's most important finding was that he found the news organizations that had the closest ties to the CIA. He said that the New York Times, CBS, and Time Inc. had been "by far the most valuable" of these groups. The CIA's media operations were made easier by the cooperation of news executives like William Paley of CBS, Henry Luce of Time Inc., Arthur Hays Sulzberger of The New York Times, and others.

Bernstein's reporting showed that the CIA's connections with journalists weren't just a few bad apples; they were part of a planned program that involved the biggest news organizations in the United States. His investigation showed that for many years, foreign branches of major U.S. news agencies had been used by the CIA to spread false information, which then made its way back into American media.

The Argument About Whether Operation Mockingbird Happened

There is still a lot of debate about whether an operation called "Mockingbird" ever existed as described, even though there is a lot of evidence that the CIA worked with journalists. There are a few main points of contention in the controversy.

Deborah Davis's 1979 unauthorized biography of Washington Post owner Katharine Graham seems to have made the term "Operation Mockingbird" more well-known. Davis said that Frank Wisner started Operation Mockingbird to fight Soviet propaganda and hired Phil Graham from The Washington Post to run the program in the media. But Davis didn't give any sources for these claims, and later investigations found no documents that showed an operation with this name.

In his 2019 book "The Rising Clamor: The American Press, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Cold War," historian David P. Hadley said that the Church Committee and Bernstein's exposé didn't give enough specific information, which made it easy for people to make up stories. Hadley says that the CIA did build relationships with journalists and news organizations, but there is no proof that there was a systematic program called Operation Mockingbird, as Davis says.

There is even more confusion because CIA documents do mention a "Project Mockingbird," but this was a different operation. The Family Jewels document, which was made public in 2007, says that Project Mockingbird was a wiretapping operation that took place between March and June 1963. It was aimed at two syndicated columnists, Robert Allen and Paul Scott, who had written articles based on secret information. This operation, which CIA Director John McCone started with the approval of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, had nothing to do with using the media to spread false information.

The Aftermath and Changes in Policy

The Church Committee's and Bernstein's investigations forced the CIA to admit its ties to journalists and make changes to its policies. When George H.W. Bush became CIA Director in 1976, the agency made a new rule: it would not hire any full-time or part-time news reporters who worked for a U.S. news service, newspaper, magazine, radio or television network, or station.

But critics pointed out that this policy had big holes in it. The CIA said it would keep "welcoming" journalists who wanted to help out for free. Many already-existing relationships were allowed to stay the same. The policy also didn't say anything about the agency's ties to news executives who could help things run smoothly without the knowledge of working journalists.

Permanent intelligence committees were set up in both houses of Congress to make sure that Congress could keep an eye on things better. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 made new laws for how intelligence can be gathered. But there were still questions about whether these changes really put an end to the practices that were revealed in the 1970s or just pushed them further underground.

Modern Relevance and Ongoing Debates

The legacy of Operation Mockingbird continues to resonate in modern discussions regarding media credibility, government propaganda, and the interplay between intelligence agencies and the press. Concerns about media manipulation have grown in recent years because of the rise of digital platforms, social media, and complex campaigns to influence people.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said during the 2024 presidential campaign that Operation Mockingbird was "alive and well today." He said that the program had never really ended and was still being used by major news organizations to sway public opinion. Fact-checkers couldn't find any proof to back up these claims, but a lot of Americans who don't trust the mainstream media agreed with them.

The argument about Mockingbird's existence and scope brings up bigger issues about how open and responsible institutions should be. Even if the program Davis talked about never existed under that name, the fact that there are so many documented CIA-media relationships makes us question how independent the press is and how well democracy works.

In some ways, the fact that people don't know much about Operation Mockingbird has made it have a bigger effect on public consciousness. The program has become a strong symbol and starting point for talks about how the media can be manipulated, how the government can spread false information, and how democratic institutions can be easily influenced without anyone knowing. Mockingbird is a documented historical fact: during the Cold War, American intelligence agencies systematically built relationships with journalists and news organizations to sway public opinion. This is true whether or not the specific details fit the mythology that has grown around it.

What We Learned and What It Means

Operation Mockingbird teaches us a lot about how the government, the media, and the public can trust each other. First, it shows how easy it is for the press to lose its independence when people appeal to patriotism and national security. Many journalists who worked with the CIA thought they were doing their duty to their country, not giving up their integrity. This shows how easy it is to break professional ethics when you put them in the flag.

Second, Mockingbird shows how important it is for intelligence operations to be open and responsible. Because the program was secret, Americans got news and analysis for decades without knowing that intelligence agencies were changing the results. Even though people know about these operations, they still don't know everything about them because many details are still secret or have been destroyed.

Third, the debate about whether or not Mockingbird exists shows how secrecy leads to speculation. Because there isn't enough documentation, the program has become almost legendary in some circles, with claims that go far beyond what is known to be true. This shows how important it is to declassify information and make history clear, not just for accountability but also to make sure that history is accurate.

Lastly, Mockingbird is a warning about how dangerous it is to mix intelligence work with journalism. Using journalism as a cover for intelligence operations not only hurt the reputations of the journalists who took part, but it also made all journalists look bad, especially those who worked in sensitive areas or foreign countries. This suspicion still exists today and has put journalists who have nothing to do with intelligence agencies in danger in some cases.

Conclusion

Operation Mockingbird is still one of the most talked-about parts of American intelligence and journalism history. It doesn't matter if there was a formal program with that name or if the term is just a convenient way to talk about documented CIA-media relationships. The fact is that during the Cold War, American intelligence agencies systematically hired journalists and built relationships with news organizations to sway public opinion and further their foreign policy goals.

We may never know the whole truth about these operations. A lot of important people have died, a lot of documents have been lost, and a lot of information is still secret. There is no doubt that the CIA and the American media had a much closer relationship during the Cold War than people knew at the time. This relationship had a big effect on public trust and democratic governance.

As Americans deal with a media landscape that is getting more complicated and full of conflicting stories and worries about false information, the lessons of Operation Mockingbird are still important. The program is a reminder that we must always be on guard to protect press freedom and that the public's right to know must be balanced with real security concerns through open, accountable processes instead of secret manipulation.

In American culture, the mockingbird is known for being able to copy the songs of other birds. The name of this supposed CIA media program, whether on purpose or by chance, turned out to be very fitting. The goal of the operation was to get American media to sing the same song as U.S. intelligence agencies. This goal was achieved much more than most Americans realized until many years later. Anyone who wants to deal with today's media with the right amount of skepticism and discernment needs to know this history.

References

- Church Committee Reports (1975-1976), U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities

- Bernstein, Carl. "The CIA and the Media." Rolling Stone, October 20, 1977

- CIA Family Jewels document (declassified 2007)

- Davis, Deborah. "Katharine the Great: Katharine Graham and the Washington Post" (1979)

- Hadley, David P. "The Rising Clamor: The American Press, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Cold War" (2019)

- National Security Council Directive NSC 10/2 (1948)

- Office of Policy Coordination documents, CIA Freedom of Information Act releases

- U.S. Senate Historical Office, "The Church Committee" historical overview

- Levin Center for Oversight and Democracy, Church Committee resources

- Various news articles from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other sources documenting the investigations and revelations