The Announcement That Shook the World

Cold Fusion: The Promise That Would Not Die

Arcane SciencesContent Disclaimer: This article contains speculative theories presented for entertainment. Readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions.

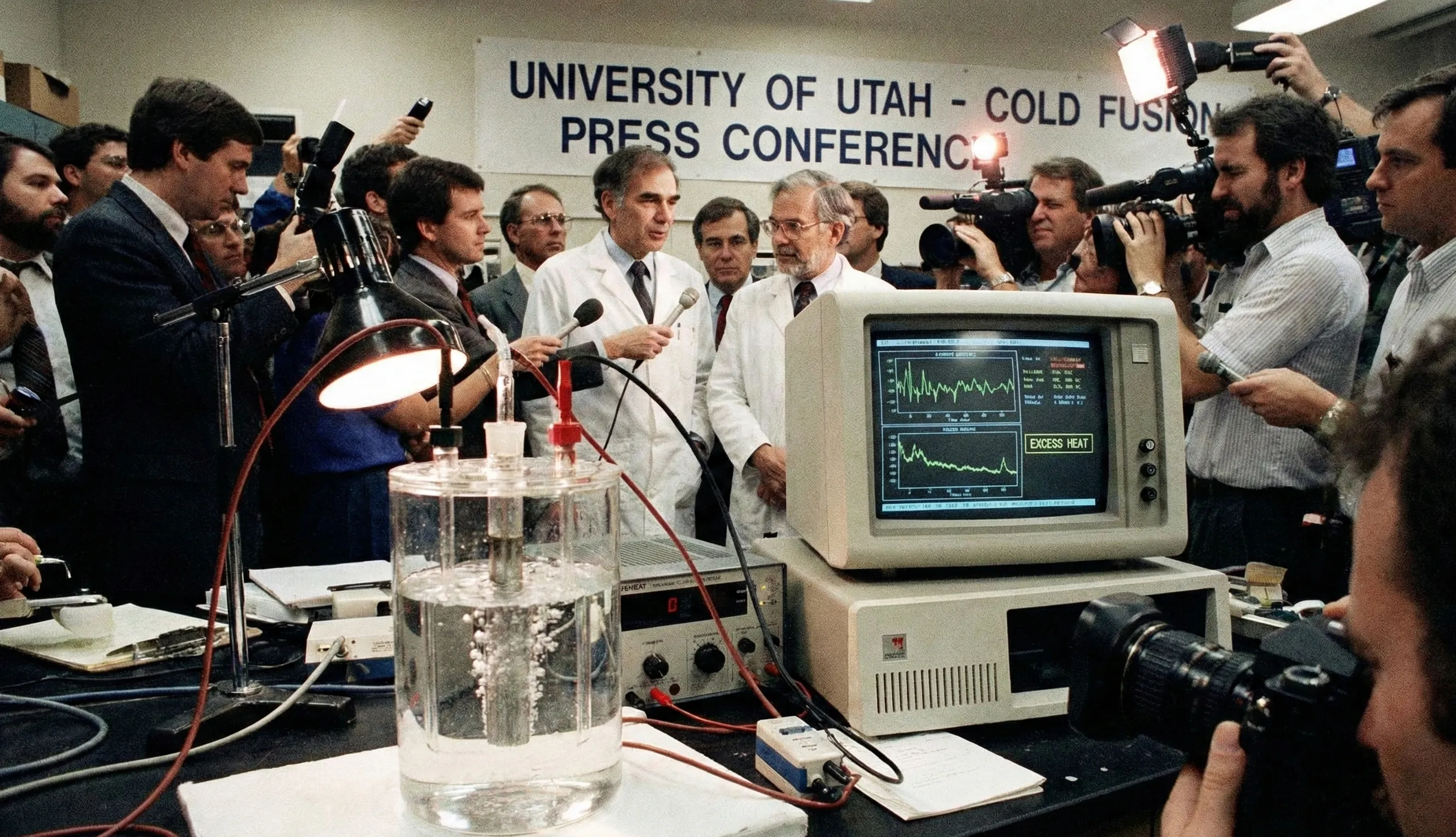

On March 23, 1989, two chemists held a press conference that would change their lives and divide the scientific community for decades. Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons announced they had achieved nuclear fusion at room temperature.

The implications were staggering. Conventional fusion requires temperatures hotter than the sun's core. Billions of dollars had been spent on tokamaks and laser systems trying to contain plasma at millions of degrees. And here were two electrochemists claiming they had done it in a jar on a benchtop.

Their setup was simple. A palladium electrode immersed in heavy water containing deuterium. Run current through it and wait. The palladium absorbs deuterium into its crystal lattice. Something happens.

Fleischmann and Pons reported excess heat. More energy coming out than going in. Far more than could be explained by any known chemical reaction. They believed deuterium nuclei were fusing inside the palladium, releasing nuclear energy.

> If true, energy scarcity would become a problem of the past. Every nation could produce unlimited clean power.

The press conference bypassed normal scientific channels. No peer reviewed paper. No independent replication. Just an announcement and a rush for priority. The University of Utah wanted credit for what could be the discovery of the century.

Within weeks, laboratories worldwide attempted to replicate the experiment. Results were chaotic. Some claimed success. Others found nothing. The same experiment seemed to work sometimes and fail other times.

The physics community grew hostile. Nuclear fusion should produce radiation and neutron emissions. These signatures were absent or far below expected levels. How could fusion occur without the expected byproducts?

By May, the backlash was overwhelming. A panel at the American Physical Society meeting declared cold fusion dead. Respected physicists called it pathological science at best, fraud at worst. Careers were destroyed. Reputations shattered.

Fleischmann and Pons retreated to France, funded by Toyota, to continue their work in obscurity. The University of Utah's technology transfer office closed their cold fusion project.

The dream seemed over. But it refused to die.