Content Disclaimer: This article contains speculative theories presented for entertainment. Readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions.

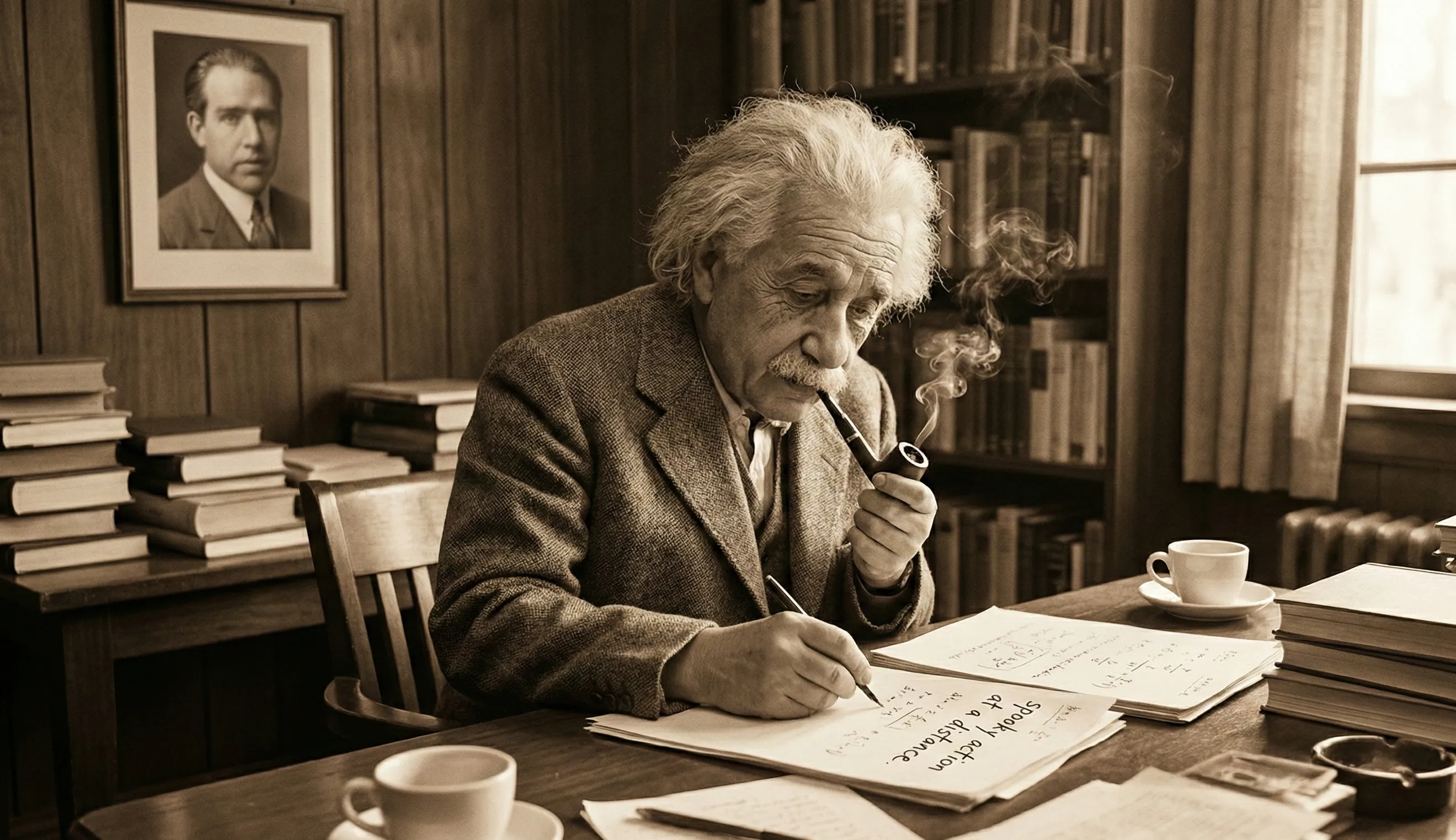

Albert Einstein did not like quantum mechanics. He helped create it. But he never accepted what it implied.

In 1935, Einstein published a paper with Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen that he hoped would expose a fatal flaw in quantum theory. The argument, known as the EPR paradox, focused on a phenomenon that seemed impossible.

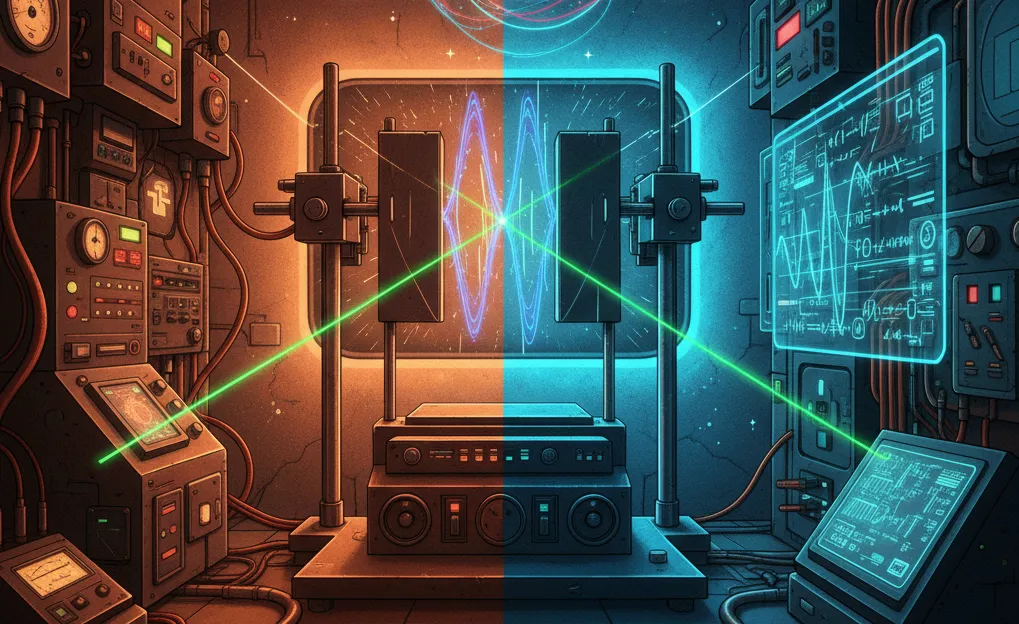

Quantum mechanics predicted that two particles could become entangled. Once entangled, measuring one would instantly affect the other, no matter how far apart they were. Not eventually. Not at the speed of light. Instantly.

Einstein called this spooky action at a distance. He meant it as an insult. The universe, he believed, did not work that way. Influences travel at finite speeds. Effects have local causes. Nothing can coordinate instantaneously across space.

The EPR paper argued that if quantum mechanics predicted such correlations, then the theory must be incomplete. There must be hidden variables, information the particles carry with them that predetermines the outcomes. The correlation would then be like two gloves packed in separate boxes. Open one and you instantly know what is in the other. No spookiness required.

Niels Bohr responded immediately. He defended quantum mechanics, though his arguments were subtle and disputed. The debate raged through the 1930s and 1940s without resolution.

Most physicists sided with Bohr, but not because anyone had proven Einstein wrong. They simply found quantum mechanics too useful to abandon. It predicted experimental results with stunning accuracy. Philosophical objections could wait.

Einstein died in 1955, still unconvinced. He believed that reality was local and realistic, that objects had definite properties whether or not anyone measured them, and that influences could not travel faster than light.

For nearly thirty years, the debate seemed unanswerable. How could you test whether hidden variables existed? The quantum predictions and the hidden variable predictions seemed to give the same results.

Then in 1964, an Irish physicist named John Bell changed everything.

Bell showed that hidden variable theories and quantum mechanics actually predicted different outcomes in certain experiments. The difference was small but measurable. For the first time, Einstein's objection could be tested.

The universe was about to reveal which of the two giants was right.