Content Disclaimer: This article contains speculative theories presented for entertainment. Readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions.

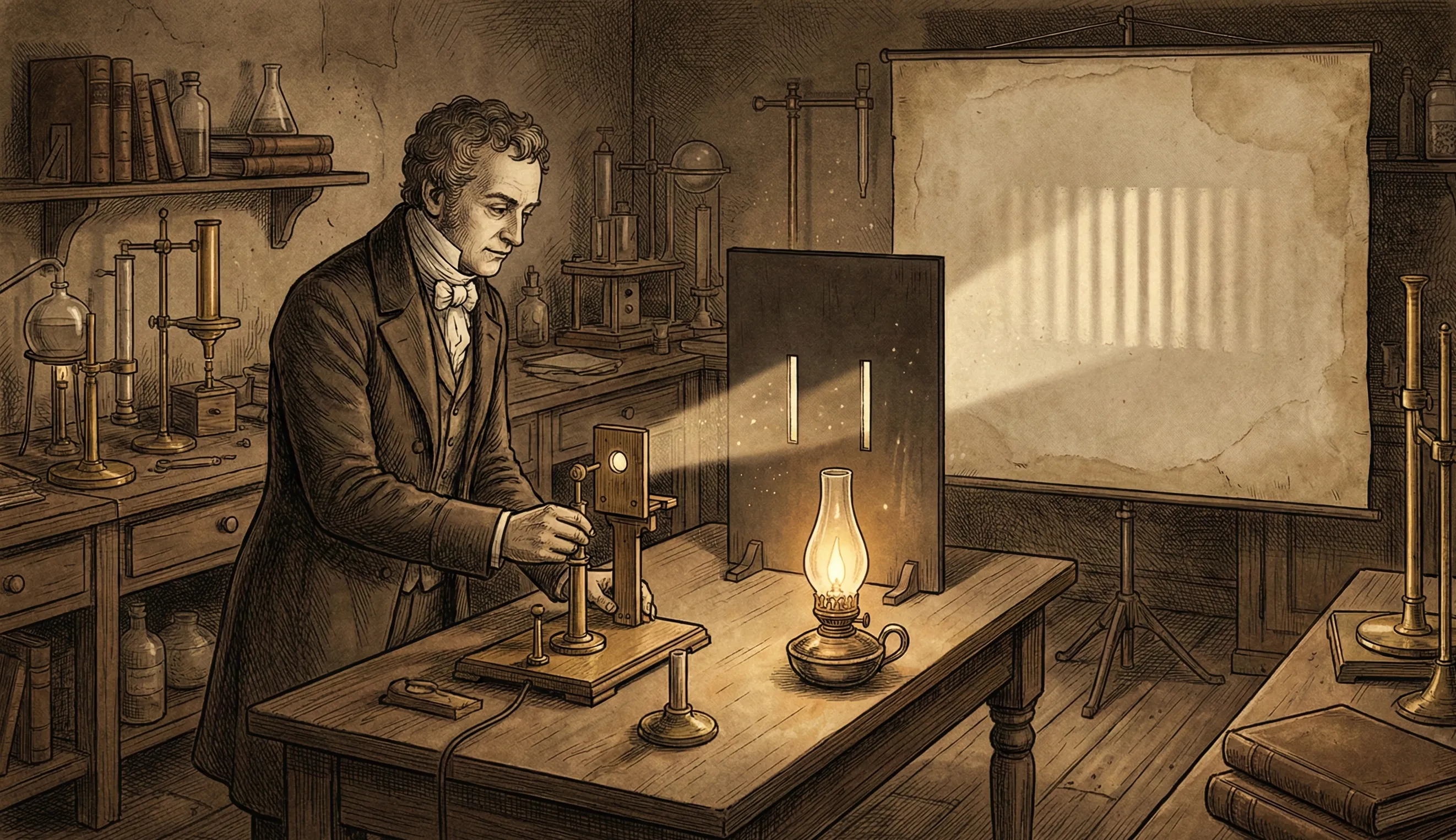

In 1801, Thomas Young did something that should have been simple. He shone a beam of light through two narrow slits cut into a piece of cardboard.

What happened next should not have happened.

On the screen behind the slits, the light did not create two bright lines as expected. Instead, it produced a series of alternating light and dark bands. An interference pattern. The kind of pattern you see when two waves meet in water.

Young had just proven that light was a wave. Not a stream of particles as Newton believed. A wave, spreading out, overlapping with itself, creating peaks where the waves aligned and troughs where they canceled out.

The scientific community eventually accepted this. Light was a wave. Case closed.

For a hundred years, that answer held.

Then came 1905. A young patent clerk in Switzerland named Albert Einstein proposed something radical. Light, he argued, also behaved like a stream of particles. He called them photons. This was not speculation. He used this idea to explain the photoelectric effect, a phenomenon that wave theory could not account for.

Light was a wave. Light was also a particle. Both statements were true. Neither could be discarded.

The scientific community did not know what to do with this. How could something be two different things at once? Waves spread out. Particles have specific locations. These are mutually exclusive properties.

In 1924, a French physicist named Louis de Broglie made it worse. He proposed that it was not just light. Everything had wave properties. Electrons. Atoms. You. Me. Everything.

The math worked. The experiments confirmed it. But nobody understood what it meant.

In 1927, two physicists named Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer fired electrons at a nickel crystal. The electrons bounced off in a pattern that only made sense if they were waves. Not particles. Waves.

The same year, George Paget Thomson achieved the same result using thin metal foils.

Electrons, the fundamental building blocks of matter, were behaving like waves.

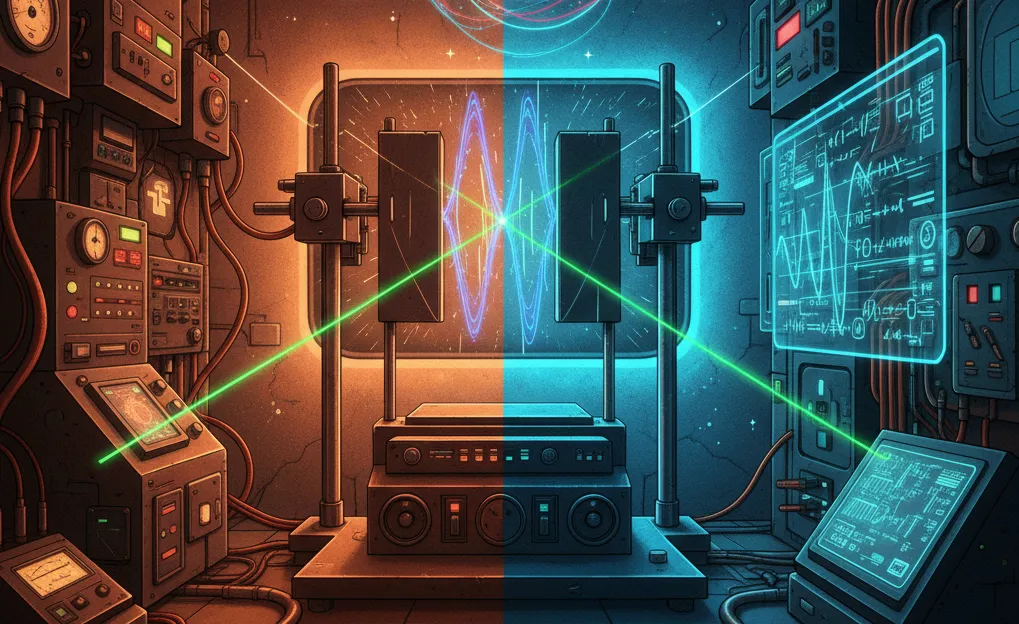

So scientists went back to Young's experiment. This time, instead of light, they used electrons. They fired electrons one at a time through two slits.

Here is where reality started to crack.

Each individual electron hit the screen at a specific point. Like a particle should. But when thousands of electrons accumulated, they formed the same interference pattern that light had produced. As if each electron was somehow passing through both slits simultaneously and interfering with itself.

One electron. Two slits. Both paths taken at once.

This made no sense. An electron is a thing. A discrete object. It should go through one slit or the other. Not both.

So physicists did what any reasonable person would do. They put detectors at the slits to watch which one the electron went through.

And then something happened that still haunts physics today.

When they watched, the interference pattern disappeared. The electrons started behaving like normal particles. Going through one slit or the other. Never both. No wave behavior. No interference.

The act of observation changed the outcome.

Turn off the detectors. Stop watching. The interference pattern returns. The electrons go back to being waves passing through both slits.

This was not a limitation of the equipment. It was not about disturbing the electrons with the measurement. Later experiments used increasingly subtle methods of detection. The same thing happened every time.

Observation. Measurement. The simple act of gathering information about which path the electron took. That was enough to collapse the wave behavior into particle behavior.

Niels Bohr called this the Copenhagen Interpretation. The electron exists in a superposition of states until it is measured. Both paths. Both possibilities. All at once. Measurement forces reality to choose.

Einstein hated this. He spent the rest of his life trying to find a flaw in it. He never did.

The double slit experiment revealed something fundamental about the universe. Reality at its most basic level does not exist in a definite state until it is observed. Particles are probability waves until something interacts with them. Until then, they are everywhere and nowhere. All possibilities superimposed.

This was not philosophy. This was physics. Repeatable. Predictable. Verified thousands of times in laboratories around the world.

The universe, at its foundation, behaves differently when you are looking.