Content Disclaimer: This article contains speculative theories presented for entertainment. Readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions.

In the indigenous Mansi language, it had a name long before Russian explorers arrived: Kholat Syakhl. Dead Mountain.

The Mansi people had avoided it for generations. Their shamans warned that restless spirits dwelled there, entities older than memory. Anyone who ventured onto its slopes without proper ritual preparation risked death. Stories passed down through the centuries told of travelers who disappeared, of voices heard in the wind, of lights that appeared in the sky above the peak.

The warnings were clear. Stay away. The mountain does not forgive.

But warnings rooted in folklore rarely stop the curious. And by the mid-20th century, the Soviet Union had little patience for superstition. Progress demanded exploration. Mountains were to be climbed, not feared.

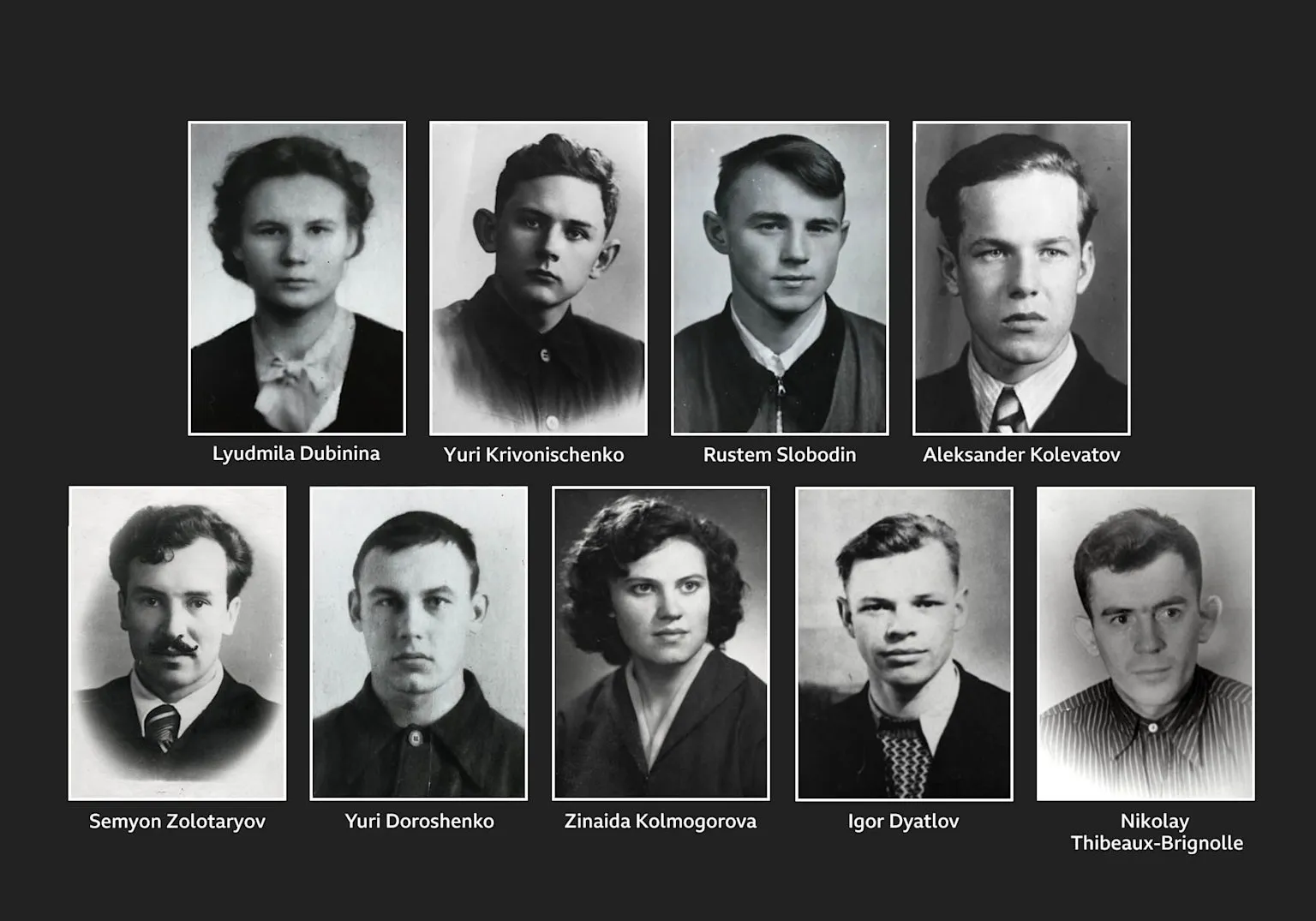

On January 23, 1959, a group of nine experienced hikers and engineering students from the Ural Polytechnic Institute set out on an expedition to summit Gora Otorten, one of the most forbidding peaks in the northern Urals. The team was led by Igor Dyatlov, a 23-year-old fifth-year radio engineering student known for his meticulous planning and leadership. His companions were equally skilled: Yuri Doroshenko, Lyudmila Dubinina, Georgy Krivonischenko, and five others, all trained mountaineers.

There was supposed to be a tenth member, Yuri Yudin. But at the last moment, he fell ill and had to turn back. That minor misfortune saved his life. It also ensured that, decades later, someone would remain to search for answers.

The group departed from the village of Vizhay on January 27. It was the last outpost of civilization before the wilderness. From there, the journey into the mountains was harsh. Weather conditions worsened rapidly. Navigation errors compounded by heavy snowstorms pushed the team off course. By February 1, they had set up camp on the eastern slope of Kholat Syakhl, roughly a kilometer below the summit.

That night, something happened.

On February 12, when the group failed to return as scheduled, their families contacted the authorities. A search and rescue operation began on February 20. Two days later, on February 22, the rescuers found the tent.

What they saw made no sense.

The tent had been cut open from the inside. The team had slashed their way out in a panic, leaving behind nearly all their gear. Food was still on the stove. Supplies were neatly arranged. Everything suggested they had fled in terror, abandoning the only shelter they had in temperatures well below freezing.

Footprints led away from the tent toward the treeline, roughly 1.5 kilometers downhill. Some of the prints indicated barefoot or poorly clothed individuals. The rescue team followed the tracks into the forest.

There, beneath a large cedar tree, they found the first two bodies: Yuri Doroshenko and Yuri Krivonischenko. Both were frozen, dressed only in underwear. Near them were the remnants of a failed attempt to start a fire. Their hands and feet showed signs of severe frostbite. Branches above them had been broken, suggesting they had tried to climb the tree, perhaps to see something or escape something.

A short distance away, rescuers found Igor Dyatlov. He was lying face-up, frozen in a half-sitting position, his arms reaching toward the campsite as if trying to crawl back.

Zinaida Kolmogorova was found further along the trail, closer to the tent. She too had been trying to return. Her body was positioned as though she had simply lain down and stopped.

Rustem Slobodin's body was discovered near her. He had a small skull fracture, but the injury was not considered fatal.

Five bodies. All dead from hypothermia. But the circumstances made no sense. Why had they fled the tent? Why were they barely dressed? Why had some tried to return while others moved deeper into the forest?

The search continued. The remaining four bodies were not found until May, when the snow began to melt. And when they were discovered, the mystery deepened into something far more disturbing.