Content Disclaimer: This article contains speculative theories presented for entertainment. Readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions.

In the ancient Sumerian language, the city was called Bab-ilu. The Gate of the Gods.

It was not a metaphor.

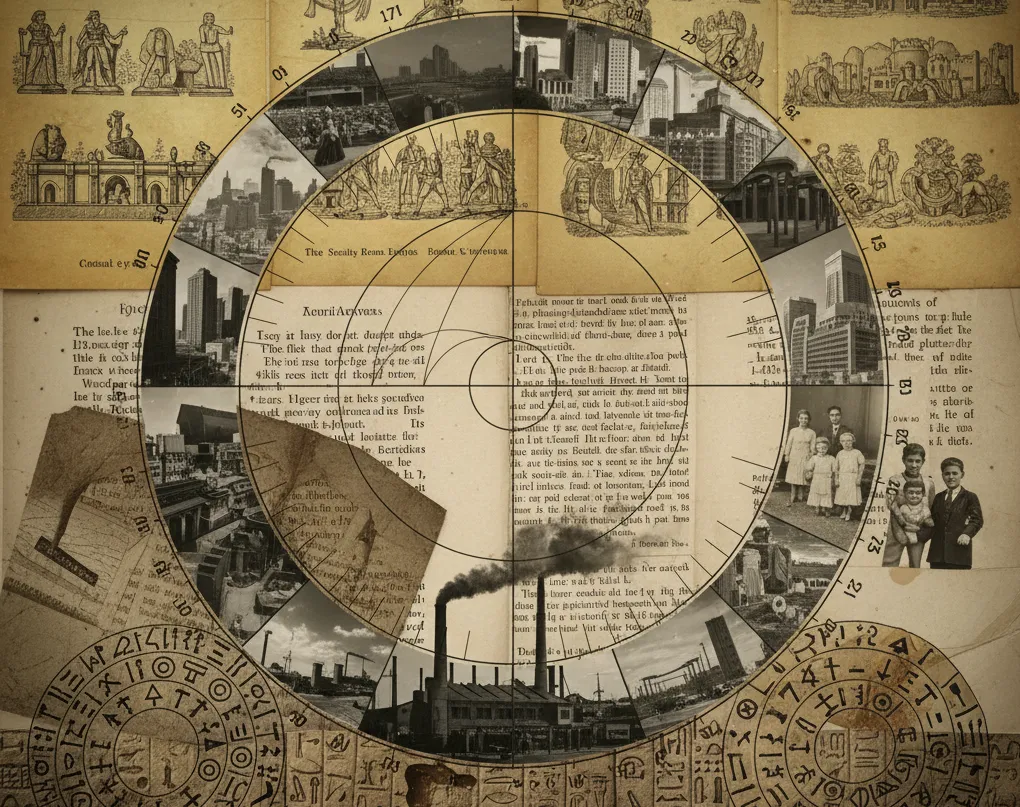

Across Mesopotamia, from the ziggurat of Ur to the ruins of Babylon, stories persisted of gateways that connected the mortal world to the realm of the divine. These were not symbolic thresholds. According to the texts, they were physical structures. Portals made of fire and light, activated by sacred words and specific celestial alignments, allowing passage between Earth and the heavens.

The Sumerians called them Kadingirra, the celestial gates. Only priests and gods could pass through. The keys were hidden in the temples. The gates opened at prescribed times, when the stars aligned and the rituals were performed correctly.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero journeys to the edge of the world and encounters a passage guarded by scorpion beings. Beyond it lies a realm where mortals do not belong. The text describes the gate as shimmering, unstable, as though reality itself bent around it.

The Book of Enoch tells of the prophet being taken from Earth and brought before a wall of fire. He passes through flames that should incinerate him but do not. On the other side, he finds himself in the presence of celestial beings, in a palace made of crystal and light. He describes the passage as instantaneous, as though space collapsed.

In Hindu cosmology, sacred sites in the Himalayas and along the Ganges were believed to contain gateways to the divine. In Zoroastrianism, the Atash Bahram, eternal flames tended by priests, served as bridges between worlds. In Norse mythology, the Bifrost, a rainbow bridge of fire, connected Midgard to Asgard.

Different cultures. Different languages. Different gods. But the same description: gateways of fire, activated by ritual, allowing passage to places beyond human reach.

Most scholars dismiss these accounts as mythology. Symbolic representations of spiritual ascension. Metaphors for transcendence.

But what if they were not metaphors? What if ancient civilizations had access to technology so advanced that it appeared magical to those who did not understand it? What if the gates were real?

The ziggurat at Ur, one of the oldest and most significant religious structures in human history, was dedicated to Nanna, the moon god. It stood as a bridge between heaven and earth, a place where the divine descended to meet humanity. But beneath its visible structure, according to fragmentary accounts, there were sealed chambers. Rooms that predated the ziggurat itself. Spaces built for purposes the later Sumerians no longer understood.

In the 1980s, during restoration work ordered by Saddam Hussein, workers reportedly uncovered hidden sections beneath the ziggurat. Chambers marked with unfamiliar symbols. Metal objects that did not match known Sumerian metallurgy. Circular structures inscribed with patterns resembling star maps.

The Iraqi military sealed the site. Archaeologists were removed. The objects were taken to the National Museum of Iraq and locked in basement storage, classified and hidden from public view.

Rumors spread among the workers. Some said they had found the Chamber of the Gods. Others described a circular gate, covered in symbols, dormant but intact. A stargate, just like the legends said.

The stories were dismissed as folklore. Exaggerations born from excitement and superstition. But the fact remained: something had been found. And whatever it was, it was important enough to hide.

Saddam Hussein was obsessed with Babylon. He saw himself as the reincarnation of Nebuchadnezzar II, the king who rebuilt the city and constructed a new Tower of Babel. He poured billions into archaeological restoration, not for tourism, but for something deeper. He believed the ancients possessed knowledge and technology that had been lost. And he wanted it back.

The question is: did he find it? And if so, what happened to it?