Content Disclaimer: This article contains speculative theories presented for entertainment. Readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions.

Somewhere in 15th century Europe, an unknown author sits down to document knowledge that shouldn't exist. Two hundred and forty vellum pages. Over 170,000 characters in a script no linguist has ever decoded. Hundreds of detailed botanical illustrations depicting plants that have never grown on Earth.

The Voynich Manuscript defies every explanation scholars have offered for six centuries. Medieval hoax? The statistical properties of the text match those of natural languages. Coded message? No cryptographic technique has cracked it. Alchemical grimoire? The content doesn't match any known occult tradition.

What remains is the impossible: a detailed encyclopedia of flora that exists nowhere on this planet.

The botanical section comprises the manuscript's largest portion. Plant after plant, carefully illustrated with roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Some show structures resembling cellular biology, impossible knowledge for the 15th century. Others display root systems that form geometric patterns no terrestrial plant produces.

Botanists have spent decades trying to match these illustrations to known species. They've failed. Not because the drawings are crude or stylized, but because they're too precise. These plants follow biological logic. They have vascular systems, reproductive structures, growth patterns. They simply don't correspond to anything in Earth's botanical record.

The coloring provides another anomaly. Medieval pigments were limited and expensive. The manuscript uses a palette that includes colors difficult to produce with contemporary techniques. More disturbing: some pigments under spectroscopic analysis show chemical compositions that don't match any known medieval source.

Someone documented an entire ecosystem that doesn't exist. Someone did it with scientific precision centuries before modern botany developed.

The astronomical section compounds the mystery. Circular diagrams show what appear to be star charts and celestial maps. But the configurations don't match Earth's sky. The central figures in these diagrams aren't the sun or moon as medieval Europeans understood them.

Some researchers argue these represent the zodiac or alchemical symbols. The mathematics don't support this interpretation. The angular relationships between elements suggest actual astronomical calculations, not symbolic representations. Calculations based on observations made somewhere else.

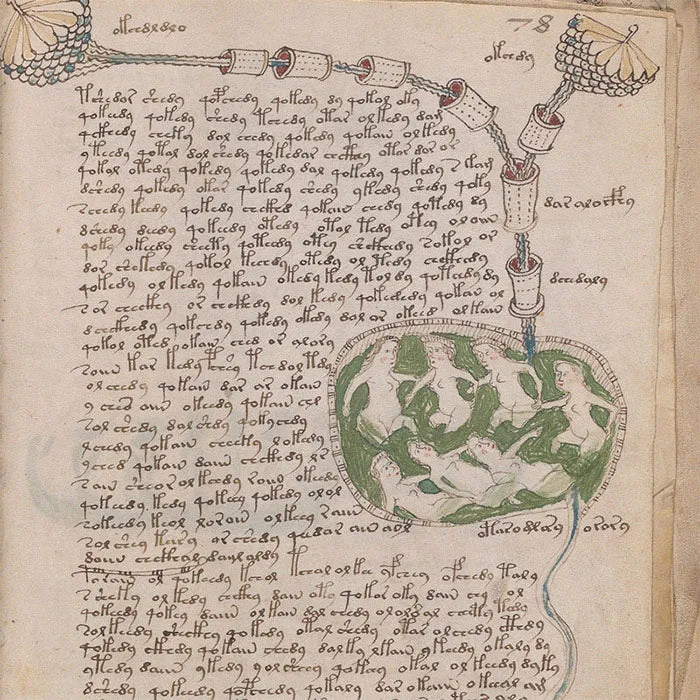

The naked women immersed in green liquid throughout the biological section have puzzled scholars for centuries. Are they bathing? Alchemical processes? The consistent green coloring and the tubes connecting various pools suggest something more systematic. Something resembling a biological cultivation system.

Modern hydroponics uses similar principles: nutrient solutions, interconnected systems, controlled environments for growing organisms. In the 15th century, this concept didn't exist. Yet here it is, illustrated in meticulous detail.

Carbon dating places the vellum between 1404 and 1438. The ink shows similar age. Whatever this document is, it was physically created in medieval Europe. But knowledge doesn't respect temporal boundaries. Information can be transcribed from older sources. Traditions can preserve data across millennia.

The writing system itself presents the deepest puzzle. Over 170,000 characters using an alphabet of approximately 20-30 glyphs, depending on how you count variants. Statistical analysis shows the text follows Zipf's law, a mathematical pattern characteristic of natural languages. The entropy matches known linguistic systems.

This isn't random gibberish. It's not a substitution cipher of known languages. It's something else entirely. A language with consistent grammar, word patterns, and structure. A language that has never been spoken anywhere else in recorded human history.

Unless it was spoken somewhere beyond human history. Unless what we're looking at isn't a medieval creation but a medieval copy of something far older. Or far more distant.

The manuscript's early provenance remains obscure. It surfaces definitively in 1639 when Prague scholar Georg Baresch writes to Athanasius Kircher, the renowned Jesuit polymath, begging for help with translation. Baresch describes it as taking up space uselessly in his library for years. Where did he acquire it? He never says.

Before Baresch, shadows and rumors. The Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II allegedly purchased it for 600 ducats, a fortune for a book. Some accounts connect it to Roger Bacon, the 13th century philosopher who wrote about flying machines and microscopes centuries before they existed. Others whisper of John Dee, the Elizabethan magus who claimed to communicate with angels in a language called Enochian.

Each connection raises more questions. Each potential author complicates rather than clarifies. The manuscript exists outside normal chains of transmission, appearing and disappearing through history like something that shouldn't be here but refuses to leave.

The question no one wants to ask: what if it's exactly what it appears to be? A botanical manual documenting plants from somewhere that isn't Earth. Written in a language from somewhere that isn't Earth. Preserved through centuries because someone understood its value even without comprehending its content.

A field guide to alien botany, waiting for humanity to develop the knowledge needed to finally read it.